Discarnate Entities: Demons, Unattached Burdens, and Intersubjective Parasites

Warning: A potential metaphysical shock ahead.

“Entities,” or “discarnate entities,” is a phrase used in shamanic and psychedelic circles to describe beings that exist outside our minds and bodies, which not only interact with us but can do us harm. Demons are the most popular phrase used in Western consciousness for the harming entities, but similar terms exist across traditions, such as jinn, dybbuk, wekufe, yōkai, and yaoguai.

In the book Chaos, Creativity, and Cosmic Consciousness, mystic and psychonaut Terence McKenna describes the cross-cultural presence of these entities:

These entities seem to occupy a kind of undefined ontological limbo. Whatever their status in the world, their persistence in human experience and folklore is striking. The phenomenon of their existence is not something unusual or statistically rare. In all times and all places, with the possible exception of Western Europe for the past two hundred years, a social commerce between human beings and various types of discarnate entities, or nonhuman intelligences, was taken for granted. This could have been as simple as the Celtic farmer’s wife leaving out a pitcher of milk for the faerie folk, or it could have taken more elaborate forms.

He proceeds to give three explanations for the prevalence of the many cross-cultural accounts of these entities:

First explanation: These entities are real but physical and represent an unclassified species that has not yet been placed in its proper taxonomic category. Examples could include the Jersey Devil, Mothman, and Chupacabra. I’ll call this position the “Cryptozoology Explanation.”

Second explanation. These entities are aspects of our psyche, temporarily freed from our egos’ control. McKenna considers this to be the position of psychologist Carl Jung and describes it as the “mentalist-reductionist” approach. I’ll call this position the “Psychological Explanation.”

Third explanation. These entities are real and nonphysical, acting as autonomous agents. This explanation is the most interesting one and the choice for “shamans, ecstatics, and so-called sensitive types.” It also radically counters the philosophical sensibilities of those with a modern Western worldview. I’ll call this position the “Ontological Explanation.”

McKenna leaves out another explanation, probably the most popular one today:

Fourth explanation. These entities are not real and can be explained through natural phenomena, which are currently understandable—or will soon be—through knowledge gleaned from the scientific process. When applying “Occam’s razor,” a principle that suggests the simplest explanation is usually the correct one, these natural phenomena emerge as the clear choice. This explanation applies materialist metaphysics and skeptical epistemology to anything outside what is perceived as established scientific consensus. I'll call this position the “Skeptic Explanation.”

Most intellectually minded people will weave between the Psychological and Skeptic Explanations. As McKenna mentioned, these individuals usually lack the experience of dealing with this phenomenon directly: :

Science has handled this problem by creating a tiny broom closet within its vast mansion of concerns called “schizophrenia,” deeming it a matter for psychologists, not the most honored members of the legions of the house of science. They have been told to “take care of this problem, please.” This is where we get the Jungian mentalist-reductionist model. What’s interesting about this model, which is the reigning model concerning these entities, is that its appeal is in direct proportion to a person’s lack of direct experience with the phenomenon that it seeks to explain. In other words, anyone who has ever encountered a discarnate intelligence knows that this is a woefully inadequate description of the phenomenon.

I have spoken to many engaged in advanced bodywork and emotional integration practices, as well as those experiencing non-ordinary states of consciousness, either through meditation or psychedelics, and they have encountered entity-like phenomena that are unsatisfying to explain using Occam's razor. As mentioned in a previous entry, “Playing Chess with Demons,” I myself have encountered unseen things that felt very real, which seemingly exist outside of me. It feels vulnerable to describe, but here are some of the experiences:

It felt like something was stalking me, accompanied by that tingling sensation that emerges when one feels they are being secretly watched. Fear began to flood my body, and “intrusive thoughts”—unwanted thoughts that don’t seem to originate from me—soon flooded my mind. In my most intense encounter, it felt like my body was in the process of being taken over completely. During my most recent encounter, it seemed as if something from above directly attacked my mind, physically latching onto my head and bringing me to my knees. I only escaped by praying and shifting my focus away from the mind, concentrating on the most silent spot in my body and making that my new focal center. I experienced an acute stress reaction for days afterward but ultimately felt spiritually strengthened by the experience.

I understand that those operating within the Psychological-Skeptic perspective will either think I am lying or will search for a coherent explanation from a psychological lens. This response is understandable, and I have explored these explanations myself. Yet, after experiencing such things, from a strictly pragmatic lens, these explanations felt impotent. They also carry great stigma and can be quite shame-inducing because sharing such experiences with polite company risks attracting the “crazy” label.

The philosopher Hans Vaihinger’s philosophy of “as if” posits that while a belief may not be empirically verifiable, it can serve as a useful fiction to help us navigate the world. Applying this philosophy to many phenomena, in general, has brought me the following benefits over the years: firstly, it’s more ontologically adventurous; secondly, it makes the world feel mysterious again (and not a dead world composed of unalive matter); and thirdly, even if wrong, it offers new insights on how to navigate reality. Applying this philosophy to my experiences and weaving it into the Ontological Explanation has given me greater agency in responding to such a phenomenon.

When discussing this phenomenon henceforth, I’ll move away from the philosophically fashionable Psychological-Skeptic perspective and work within the Ontological Explanation, writing as if it were true. However, I recommend keeping a skeptical hat close by for those new to whatever these entities are and who may be terrified by the prospect and consequences of their reality.

I am not a materialist, but I think the corresponding skeptical worldview offers an “ontological safe space” when things get too weird, nothing weirder than bumping into discarnate entities in the night. While adopting such a worldview may disenchant the world, in my experience, it can temporarily numb one from experiencing such weirdness.

Thanks to my “transperspectival” proclivities, I desire to explore many perspectives on a phenomenon; hence, I have explored various perspectives on these discarnate entities. My favorite perspectives are demons from Traditionalist Catholics, “unattached burdens” from Internal Family Systems, and “intersubjective parasites” from post-rationalists, presented by Evan McMullen, The Stoa’s previous Philosopher-in-Residence.

I’ll explore these discarnate entities through these various perspectives via “private philosophy” sessions at The Stoa, perhaps with you. I’ll focus on the harming entities first, as I sense doing so will be high leverage for existential wayfinding. However, there are friendly ones as well.

If there be demons, then there be angels.

There will be a private series at The Stoa featuring at least four guests:

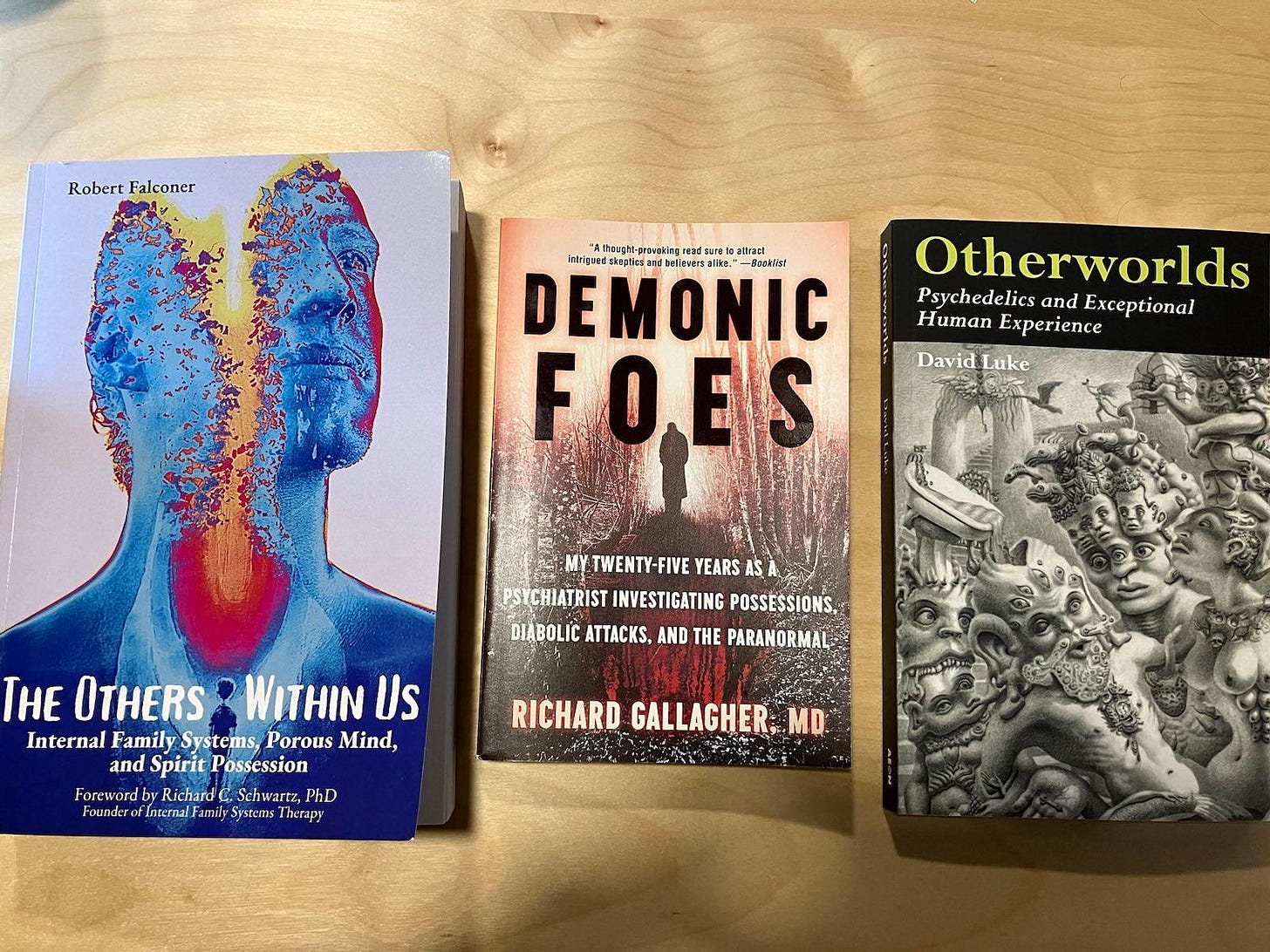

Robert Falconer, an Internal Family Systems therapist on unattached burdens.

Richard Gallagher, a psychiatrist on demon possession.

David Luke, a psychologist and psychonaut on DMT entities.

Sean Esbjörn-Hargens, an Integral theorist on non-human intelligences.

We may also have weekly sessions over a month, reading the following material together:

Also, we may revisit Evan McMullen’s series at The Stoa on “intersubjective parasites”:

These sessions may not be posted publicly. In general, The Stoa will engage in “private philosophy” for season five, and for this series in particular, we’ll be selecting attendees sensefully to prevent any entities from showing up.

The spirit of the series is to find others who would like to cultivate a bespoke communal theory and practice that is practically and philosophically responsive to this phenomenon. If you want to be considered as an attendee, members of Less Foolish can apply. More info is behind the paywall.