2025. The year we get our shit together. The art of getting one’s shit together should not be underestimated. It tastes better than that donut you want to eat, it enlivens more than the Netflix show you want to stream, and it has greater meaning than the next thing you are pulled to scroll on the screen. Last week, I recommended a discipline approach that slowly integrates wise practices in one’s life.

For example, instead of jumping into an intense hour-long workout, start with 5 minutes, and each week, incrementally increase the minutes. You will not get tremendous amounts of attention posting yourself working out a few more minutes, but that is the whole point. Discipline should be boring, bespoke to where you are at in life. Besides, one should not be feeding the screens with every little detail of their lives.

This approach is what productivity author Cal Newport calls the “discipline ladder”—overcoming small personal challenges and incrementally increasing the challenge. This approach helps acclimatize one to difficult activities. Another practice Newport recommends to getting one’s shit together is so basic but surprisingly overlooked—having a schedule. If you do not have a schedule, and sophistication in using it, then forget engaging in any advanced transformational practices with any reliability.

I hear stories of people living in monasteries, becoming super disciplined with their spiritual practices, and fall back into bad habits when they leave. I believe this is because they are not responsible for their own schedule when in a monastery. It is decided for them, hence they do not become proficient in one of the most central spiritual relationships in life: being in a good relationship with time.

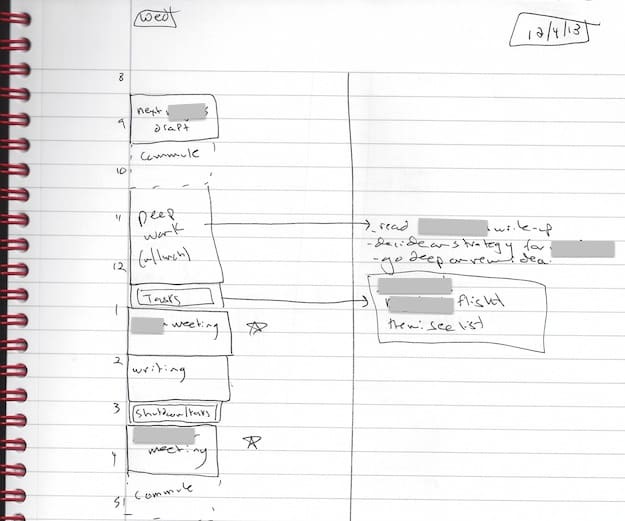

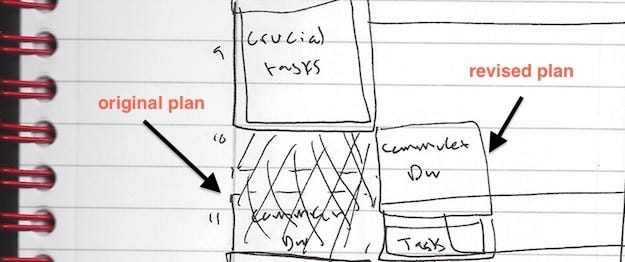

To get better at scheduling, first implement the basics: 1) get a calendar and 2) start what Newport calls “time blocking,” a practice where you allocate blocks of time in your calendar dedicated to specific activities. Here is an image of his time blocking from an early blog post where he introduced this practice:

It takes time to get good at time blocking, and one will never be perfectly loyal in doing what they plan; circumstances and opportunities arise, demanding one to break their blocks. These occurrences are why Newport recommends revising your blocks throughout the day.

After creating a schedule and implementing time blocking, you may find yourself constantly revising your blocks—not due to circumstances outside your control, but because you feel fatigued and lack energy. Awareness and skill in what is known as “personal energy management” is crucial. Understanding your body and knowing what makes it come alive or feel depleted are essential to the project of getting one’s shit together.

Personal development coach Sahil Bloom’s “energy calendar” is one approach to becoming more aware of one’s personal energy.

The energy calendar is a complementary upgrade to time blocking. At the end of the day, you review your time-blocked schedule and assign an energy level to each block. Sahil breaks it down as follows:

Green = Energizing

Yellow = Neutral

Red = De-energizing

At the end of the week, you get a bird’s-eye view of what brought energy and what took it away, informing how to adjust next week. I do not practice this method because I find it unnecessary and biased toward high-agency people who are already disciplined but not attuned to their body. It caters to a high-achiever worldview that flirts with burnout. Instead, I recommend something most self-help literature fails to address: know what ontological mode you are in.

Psychologist Eric Fromm introduced the terms “having mode” and “being mode.” The former involves acquiring something for its instrumental value—viewing things as a means to an end and aiming to change what is. The latter involves surrendering to something for its intrinsic value—viewing things as an end in itself and aiming to embrace what is.

The having mode is needed to accomplish things big and small; without it, humanity will not survive. The being mode is needed to connect to what is most sacred, bringing us meaning; without it, our humanity will not survive. Cognitive scientist

recently popularized this distinction, emphasizing what he calls “modal confusion”—confusing which ontological mode one is in.In essence, people try to meet their being mode needs through the having mode. Having sex to be in love is one example Vervaeke uses. An adjacent challenge can be called “modal tyranny,” where one mode dominates a person’s entire life. When this occurs, not only does a person confuse the modes, but they also live an unbalanced life.

In the entry “The Virtuous Mean Between Time Drunkenness and Work Martyrdom,” I contrasted “work martyrs” (popularly known as “workaholics”)—those who sacrifice their well-being (and ultimately the well-being of others) for their work—with “time drunks,” a term used by Underearners Anonymous to describe people with chronic procrastination problems and poor time management.

Work martyrs live in the having mode, leading to burnout. Time drunks live in the being mode, leading to a feeling of being stuck in life. Both live in corrupted versions of the modes. Having mode without being mode may lead to socially-improved success and status, but it invokes an internal emptiness: a “hungry ghost” vibe that desperately seeks out more validation to fill the void. Being mode without having mode may lead to moments of spiritual timelessness, but it quickly devolves into shame-masking pleasure-seeking: a wallowing in emotional pain with no agency to escape it.

The art of getting one’s shit together involves both modes—not in a perfectly balanced 50/50 ratio, but in an appropriate balance that aligns with where the person is in their life. Maybe the being mode needs to be accentuated during a period of creative discovery or emotional healing, or perhaps the having mode does to launch a project or to put out some professional fires. One can use their schedule to underlay their time blocks, indicating which mode they are in. Here is how my modes are presently balanced:

Sunday: A full day in being mode. Camille and I go to church, digitally fast (no screens for the day), relax, and spend quality time with those we love.

Monday–Friday: From 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., I’m in having mode, where I exercise, write, work on projects, and accomplish various tasks. From 6 p.m. until bedtime, I usually focus on reading.

Saturday: From 6 a.m. to 12 p.m., I dedicate time to philosophical inquiries and preparing for the week ahead. The rest of the day is set aside for being social with friends and family.

The modes are never perfectly divided. For some activities—like writing and inquiries—I consider myself within the purview of the having mode, but during the activity I imbue a sense of timelessness, thereby entering the being mode. Despite these nuances, I find that knowing in advance which mode I am in helps immensely.

When in having mode, I am sharp because my will is narrowed; I am outward-looking, aiming, and enjoying the accomplishment of things. When in being mode, I am supple because my soul is open; I am inward-looking, yielding, and enjoying being with what is.

Being in a good relationship with time is not about controlling it to get more done. It is about knowing when to be in time and when to experience life as timeless. Discerning between these modes, and weaving in and out of time, is what makes getting one’s shit together an art form.

If you have any questions, insights, feedback, or criticism on this entry or more generally, message me below (I read and respond on Saturdays) …