This entry is part of a series on “Wise Agency”: Part 1. How To Win Friends and Get Things Done ... With Wisdom? Part 2. High Agency to Wise Agency.

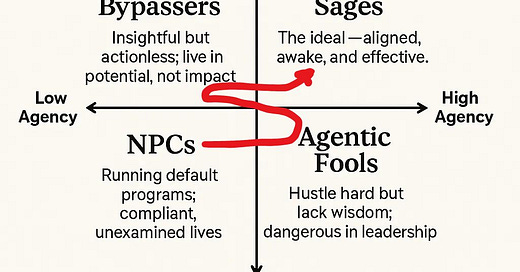

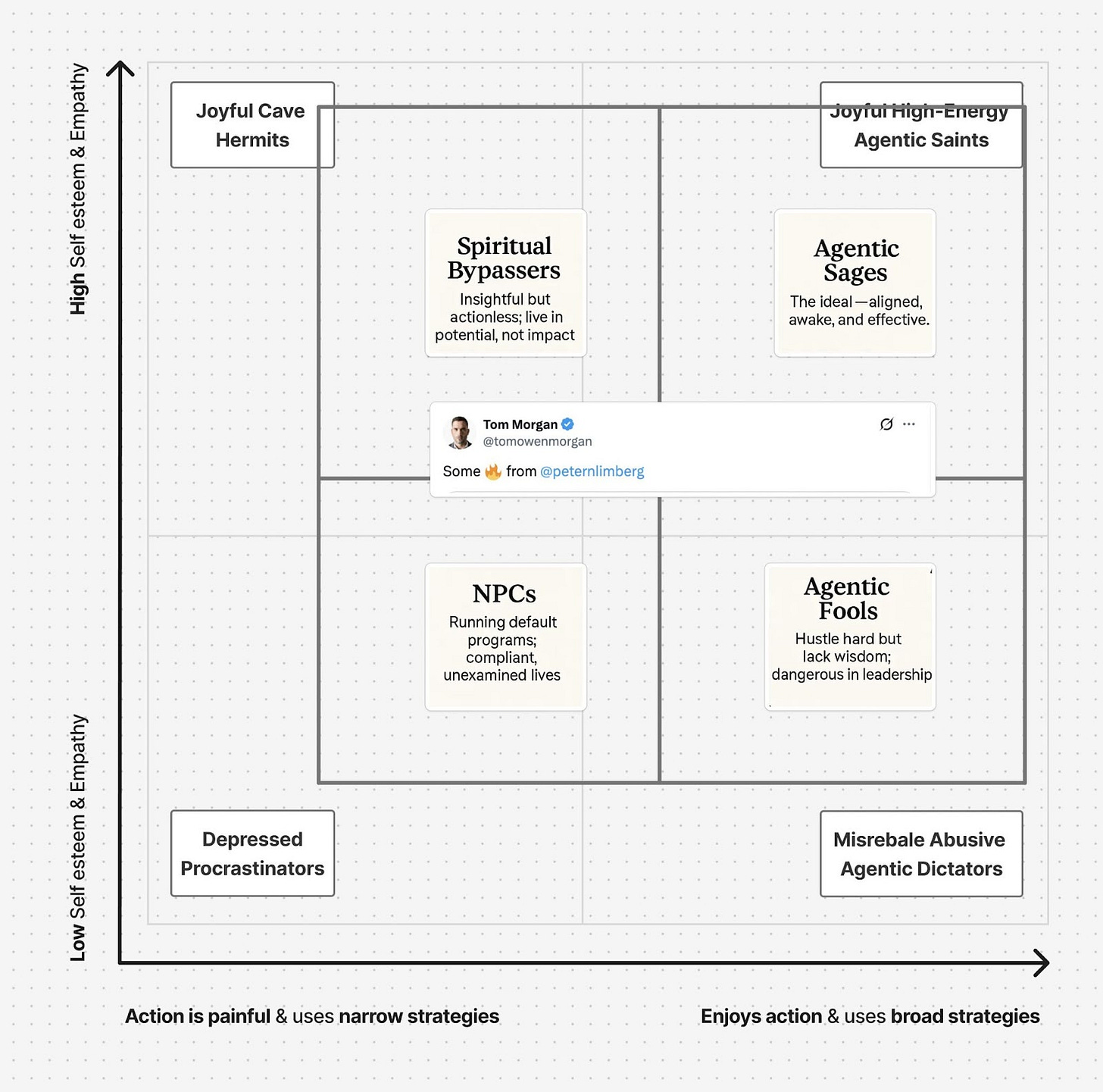

I wrote an entry last week called “How to Win Friends and Get Things Done ... With Wisdom?”, wherein I created the following 2×2.

The main reason I wrote the entry is because the word “agency,” or “high agency,” is all the rage today. Just go search the term on X and you’ll see what I mean. I like the phrase, but in addition to people being definitionally muddled about what it actually means, it’s often presented as the thing that will make everything perfect.

It’s not.

I’m not attached to the naming convention of the 2x2 and mainly created it to point out a simple truth: you can have high agency in a wise way or in a foolish way, and having the former is better than having the latter.

This point seemed to resonate with others.

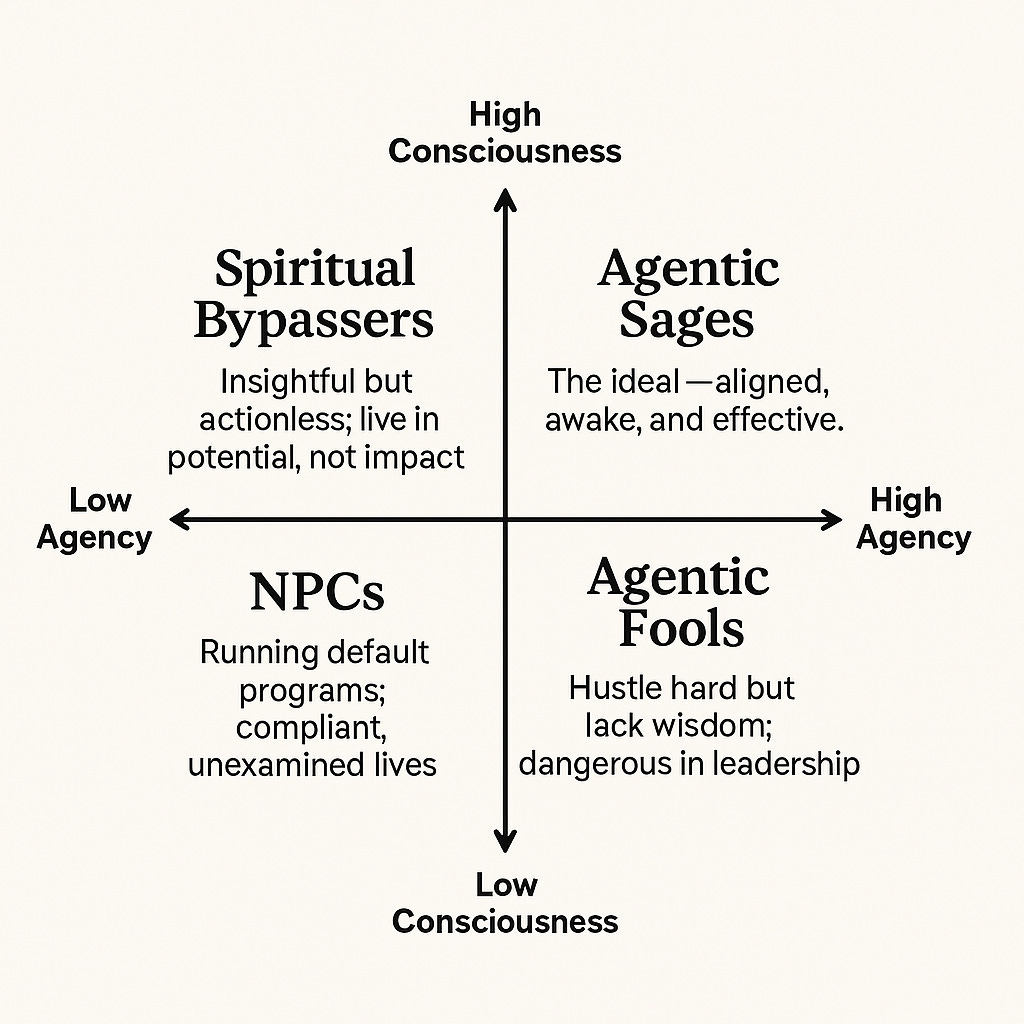

, creator of (LE), a group whose purpose is to cultivate wise agency, tweeted the 2x2 last week, and it has been memetically travelling since., an entrepreneur and host of EvolutionFM, added a trajectory to the 2x2—one that many people, including myself, go through...Exactly! I responded to Scott…

It maps to my personal journey.

NPC. You don’t take the “blue pill”; you’re born into it.

Agentic fool. Unexamined success = unquestioned “good.” Hustle, hustle, hustle until burnout.

Spiritual bypasser. A spiritual emergency happens. Aliveness. A new way of being opens up. You overindex on it. It becomes impotent.

Glad to be finding others who are also stumbling toward wise agency.

Like Scott, I now have my sights set on becoming an Agentic Sage, stumbling my way toward it with others.

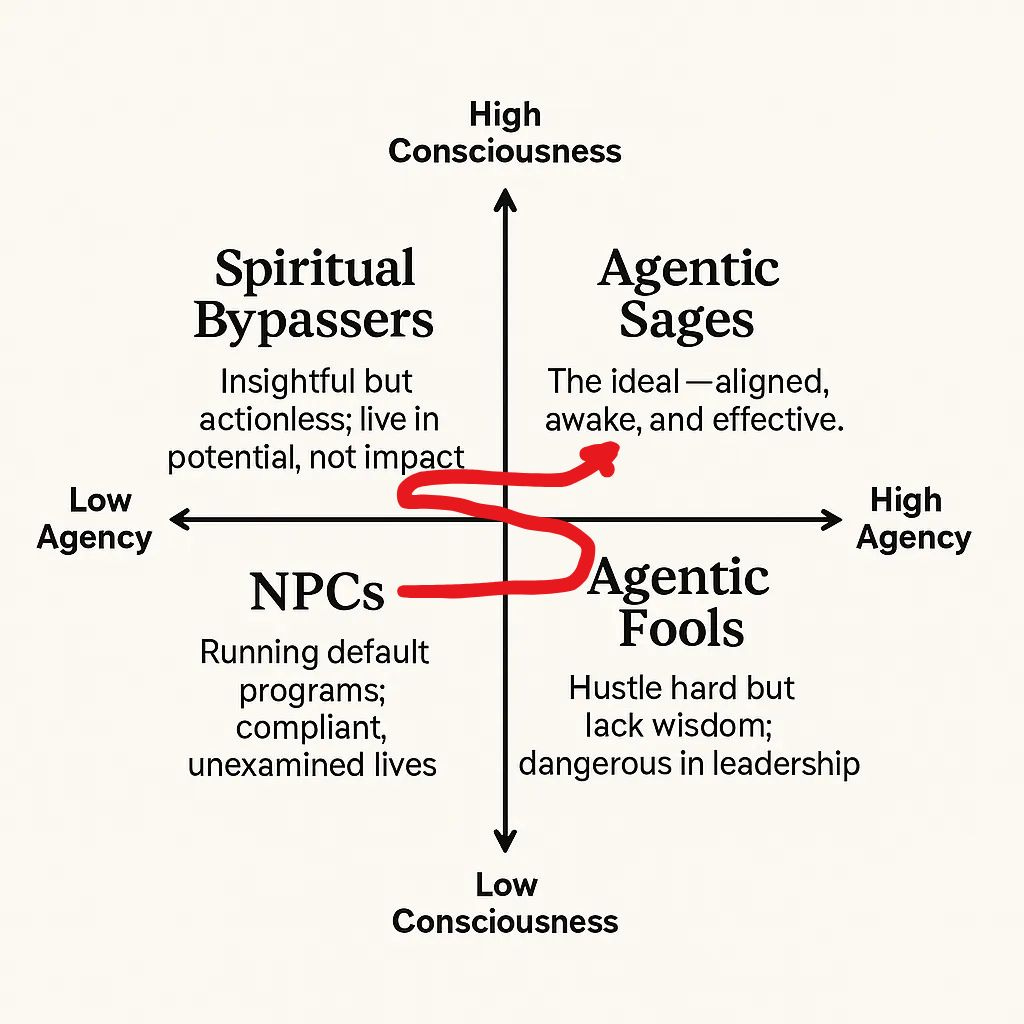

Integral thinker Matt Kreinheder had a similar take, but saw the 2x2 through the lens of “Spiral Dynamics” (a developmental theory that states human values and worldviews move through different stages, increasing in complexity).

Lastly,

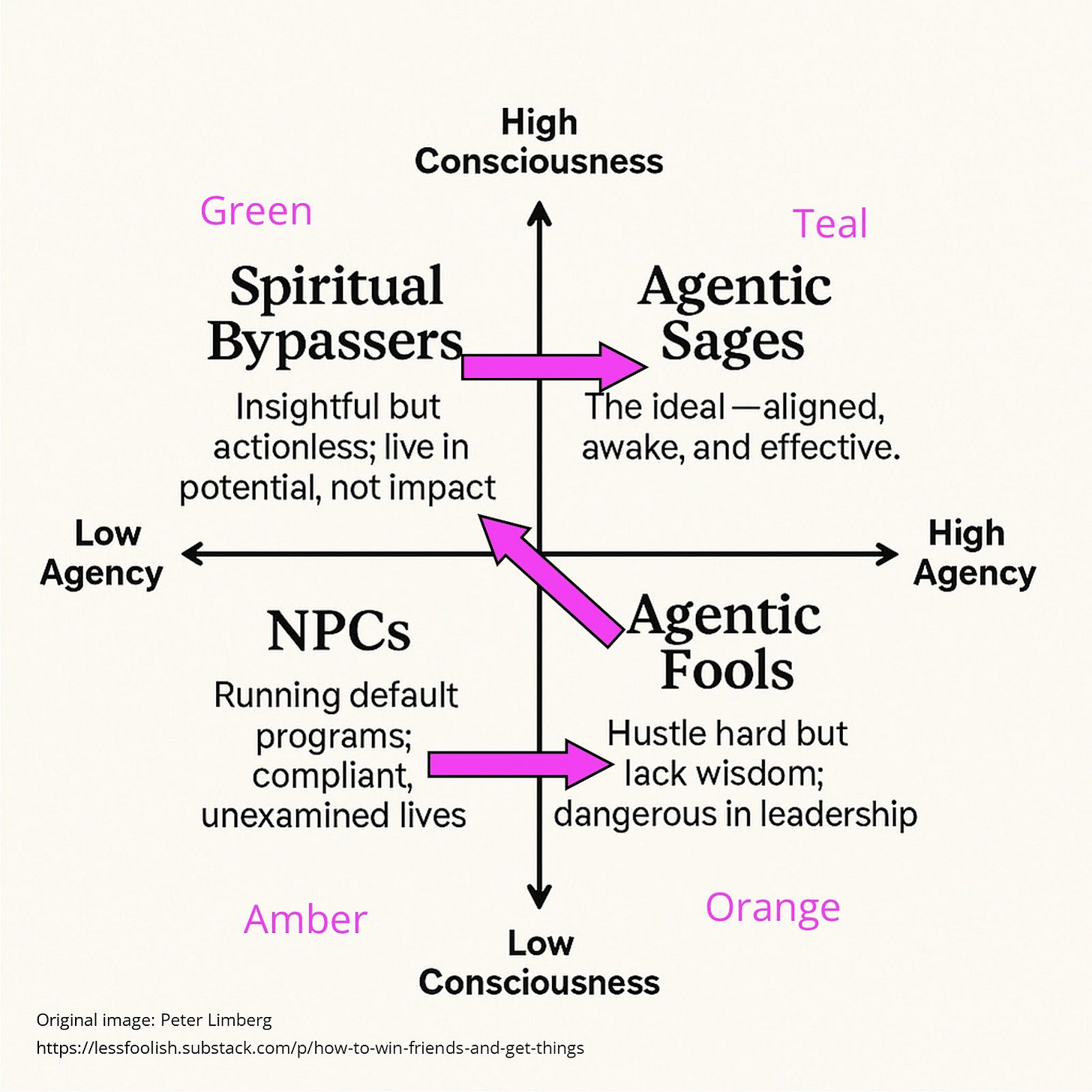

, a designer and entrepreneur embedded in the TPOT scene, took the essence of 2x2 and renamed the quadrants to something that resonated more with him.Christopher is creating a “TPOT Agency School,” which is starting with an opening conference in Berkeley in 2026. And, like Tom with LE, he sees the aim of the school as the cultivation of wise agency. I connected with Christopher, and it looks like I’ll be speaking at the conference.

Ah, the beauty of the internet.

What I like about this travelling 2x2 meme, and the various resonant tweaks people are making, is that it tells me a new skill attractor is needed: one beyond the fashionable notion of high agency we see today.

So, what is high agency?

As readers of Less Foolish know, I like to be clear in my definitions and to create “based” ones (see: “Based Definitions: A Philosophical Practice”)—self-created definitions that resonate with my body and are propositionally coherent. I am in full alignment with the quote often attributed to Socrates:

“The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms.”

I’ll aim to get definitionally clear on what high agency is, then sense into what wise agency could be.

High Agency

Different academic disciplines have different takes on the word “agency”:

Philosophy sees agency as the capacity to act intentionally and rationally to bring about change in the world.

Psychology views agency as a person’s capacity to exert control over their environment and experience a sense of ownership over their actions.

Sociology understands agency as the exercise of individual autonomy within the constraints of social structures.

All good, but I believe the source of the recent “high agency” meme is LessWrong, the “philosophers” (aka applied rationalists) who have influenced the Silicon Valley scene the most. They define agency as:

“Agency is the ability to take actions which one's beliefs indicate would lead to the accomplishment of one's goals.”

A recent popularizer of “high agency” is

. He does not define it, and instead claims it’s one of those “I know it when I see it” traits. He suggests that high agency is best illustrated in the following meme:I agree. Additionally, it can also be perceived through the newfound mantra of high agency enthusiasts that is making the rounds on X:

“You can just do things.”

Essentially, one does not have to wait for permission to do what they feel called to do—they can just do it, which is more true now than ever with AI agents at their beck and call.

However, I still believe good definitions are needed, because without them, one risks overextending the reality of what the definiendum is and its importance.

Sensing into all the above takes, the following aspects are clearly at play: taking action, getting things done, and navigating complex constraints. Hence, my newly provisional definition of the hard-to-define word agency is:

Taking action toward getting things done despite complex constraints.

High agency, as opposed to low agency, occurs when someone becomes skilled at doing this, passing a certain threshold that more reliably leads to results.

I’ll focus on the “complex constraints” aspect of the definition because it is especially relevant for those who are fond of this phrase. An important framework I recommend for understanding complexity and how to act within it comes from sensemaking legend

.His Cynefin Framework has five decision-making domains:

A highly agentic person can operate in each of these domains. The people who like to use the term “high agency” on X are typically those who do operate, or feel called to operate, in complex domains, such as product managers and startup founders. That is why I included the complex dimension in the definition.

Yes, of course, high agency is a powerful trait, something that can indeed move the world.

However, the world can be moved in the wrong direction. One can take the wrong actions and achieve the wrong outcomes, no matter how impressive the accomplishment or how complex the task.

In essence, agentic fools exist. Examples mentioned in the previous entry include Elizabeth Holmes (Theranos), Adam Neumann (WeWork), and Billy McFarland (Fyre Festival). Each displayed high agency:

Holmes raised over $700 million and created $9 billion in company valuation.

Neumann raised billions and scaled WeWork into a global coworking brand.

McFarland created massive hype through influencer marketing and sold out a luxury music festival.

However, each experienced a fall from grace:

Holmes lied about her product and misled investors, doctors, and patients (and everyone, really). She was convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison.

Neumann’s God complex got the better of him. WeWork’s valuation collapsed, losing $39 billion in perceived value, and he was forced out as CEO.

McFarland delivered a disastrous event with no food or artists, committed wire fraud, and was sent to prison.

The high-agency proselytizers might argue that these individuals did not display full agency. However, if we are operating on the following definition—“taking action toward getting things done despite complex constraints”—they did display a great deal of it. I don't think agency is what they lacked. What they lacked was integrity, ethics, and wisdom.

Many other people are expressing agency and are successful in the eyes of others, but they may be doing so foolishly, and simply haven't been “caught” yet. Christopher’s use of the phrase “Miserable Abusive Agentic Dictators” in his repurposed 2x2 is apt. One can be agentic and cruel, creating ethical externalities that ripple through society in ways that are hard to see, but deeply felt.

In essence, agency is not enough.

Enter wisdom.

An even more difficult word to define.

Wise Agency

I think the 2x2 spread memetically because “high agency” currently has cachet.

Wisdom, less so.

This is starting to change. I labeled the top-right attractor “Agentic Sage,” which nicely contrasts with the quadrant below it—the “Agentic Fool.” A standard dictionary definition of a sage is “a person who is regarded as being very wise.” Stoics and Daoists both use the term, and the sage is central to their philosophies. While they have different understandings, both agree that the sage is wise.

Like the Stoics and Daoists, I want to put my focus on wisdom so that a “wise agency” can emerge. This would mean people take the right action and get the right things done, in whatever domain they find themselves.

So, what is wisdom?

When someone asks, I usually tell them to read my “Wisdom Moment” entry, which gives a simple yet embodied example of what I believe wisdom looks and feels like. However, for those who require more propositional grounding, a definitional understanding will help.

We can start with philosophy, the supposed “love of wisdom.” Yet when modern academic philosophers were recently surveyed, wisdom was not in the top spot when they were asked about the aim of philosophy.

Disappointing, but not surprising, given what’s called the “epistemic turn” (a focus on propositional knowledge in disembodying ways) in philosophy since René Descartes. Psychologists today are actually the ones who place more emphasis on the “construct” of wisdom. Here are some definitions from modern psychologists:

“The understanding which is essential to living the best life.” - Richard Garrett

“The ability that enables the individual to grasp human nature, which operates on the principles of contradiction, paradox, and change." - Vivian Clayton

“The power of judging rightly and following the soundest course of action, based on knowledge, experience, understanding, etc.” - Robert J. Sternberg

“Practical wisdom consists in the capacities needed to make good judgments about what matters in life and to bring one’s actions into accordance, insofar as this is in one’s control.” - The Rosewood Report

“A relatively late-emerging form of cognitive/affective understanding that grows dialectically from earlier analytic and synthetic skills and integrates these into a broader fabric of reflectivity.” - Masami Takahashi and Willis F. Overton

I don’t really like any of these. When it comes to psychological researchers, I prefer Igor Grossmann’s definition:

“The meta-value that adjudicates between all other values.”

Holding a certain value, or “attentional protocols,” as axiologist

understands them, places one’s attention on a particular aspect of life. Your values influence how you see the world and how you move through it. Wisdom, as the meta-value, gives one the capacity to zoom out from the ecology of available values, including agency, and choose the appropriate one to meet the moment.A simpler, more elegant definition, still compatible with Grossmann’s, comes from Tom Morgan of LE:

“Know what to do, and when.”

I love parsimonious definitions, which is why I favour Tom’s over the academic ones. My own definition is similar but has a jazzier tone, more in line with the Less Foolishism my readers are accustomed to:

Existential wayfinding.

“Existential” here means what is deeply important to one’s life, and “wayfinding” means finding one’s way. I find the literature on ordinary wayfinding, the kind where one navigates physical environments, quite helpful in understanding wisdom.

As I described before: “Wayfinding is the art of finding one's way in physical space, and we can view ‘existential wayfinding’ as the art of finding one's way in life.”

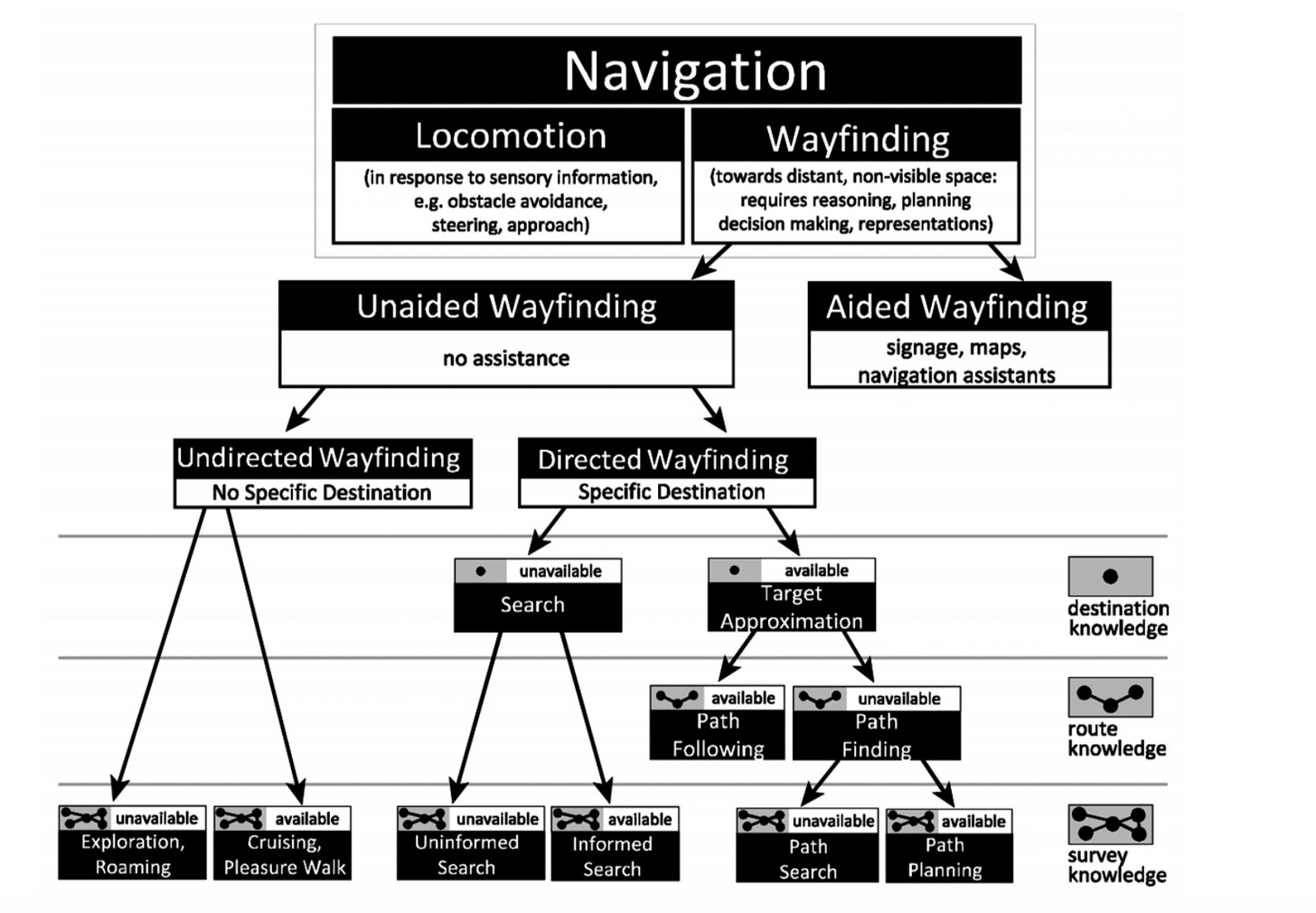

Here is a useful diagram I often return to:

In the diagram, navigation is bifurcated into locomotion and wayfinding. The former refers to how the body coordinates within local space, while the latter involves decision-making and operates across both local and distal spaces.

The next divide is between aided and unaided wayfinding. Aided wayfinding uses tools for navigation, such as signs and maps. With existential wayfinding, today these tools might include podcasts or Substack posts. On the other hand, unaided wayfinding in both physical and existential forms requires one to stumble their way forward.

The next divide is between directed and undirected wayfinding. The former is where the value of agency is most needed. It has a clear enough aim: a goal, a task, a project. The latter does not. There is no specific destination: going on an adventure is the point. Exploration becomes the goal. Getting lost becomes a way of being found.

The challenge with those who promote high agency without wisdom is that it risks creating what philosopher Michael Oakeshott calls the “deadliness of doing.” Not everyone always needs to be taking “action toward getting things done.” Sometimes, they need to let go, relax, and face what lies beneath that subtly compulsive urge to accomplish or control something.

In short, if one presents high agency as the supreme good, rather than as one value within a broader ecology of values, they risk becoming an agentic fool.

So, what is “wise agency”?

To modify the above definition of agency, it is:

Taking the right action toward getting the right things done, despite complex (and clear, complicated, chaotic, or confused) constraints.

It also means knowing when not to be agentic.

It means knowing when to just be.

Agree? Disagree? More confused?

Good. Come to Collective Journalling and create your own “based definitions.”

For upcoming sessions at The Stoa, check out our website.

For one-on-one “coaching” inquiries, email me at thestoa at protonmail dot com for availability and payment options.