It started to rain a few hours before the event, and I wasn’t sure many would show up. I kind of liked the vibe: a dark, cold, wet Monday night in Toronto, where we’d discuss the politics of hope. I tuned into the group gathering soon and the questions we’d explore:

Can we have a politics of hope? Or is politics too material for hope? Or is hope too spiritual for politics?

I was getting my hair cut beforehand, and the spirit of the question was living with me. I really enjoy my barber’s mind. He’s philosophical but unpretentious, which I imagine is because he doesn’t associate with those concerned with intellectual status signaling. A true blue-collar autodidact. We started talking about hope, which led to a conversation about God.

He’s an atheist and seems optimistic about rapid technological development. He was enthusiastic about Google’s new quantum computing Willow chip, believing that these computational capabilities could accelerate AI training, leading to the massive neural networks required for AGI (artificial general intelligence).

These advancements, he argued, would create real-life simulations akin to our reality, like Matrix-style environments. Moreover, he said AGI would create “nested simulations,” or realities within realities, making base reality unknowable to us and raising serious questions about whether we are simulated beings ourselves.

Listening to all of this gave me anxiety. He continued, explaining that the “technological singularity,” where exponential technological growth results in irrevocable transformation, may soon be upon us. He mused that this would allow AGI to be seen as a God, which he seemed pleased with. He conveyed that the world is so messed up that we need a God to bring order.

I found this disposition interesting and confirmed one of my hypotheses: an atheist’s dirty secret is that they long for God so much they desire to create one. I wondered to myself: why not just believe in God now?

I thanked him for the fresh cut and stimulating conversation, grabbed a pizza slice, and then Ubered over to The Beguiling, Toronto’s famed comic shop where the event was being held. I met our gracious venue host, Alex, and my co-host for the event, Khalil. I ordered delicious COPS donuts and prepared the limited-print zines to hand out when guests arrived.

Zines are making a comeback among intellectual hipsters (see

on zines), and it seems like everyone is creating them now. I think they add a nice touch to in-person events, especially if they are positioned as “antimemetic.” By this, I mean asking that they not be replicated digitally so they do not memetically spread online. The animist in me likes the idea that whatever happens in person stays in person, and that the spirit filling the room is imbued through the group’s touch on this little physical artifact: a spiritual keepsake one can hold onto forever.Around 30 people arrived, the donuts and zines were passed around, and we gathered in a circle amidst superheroes and hentai drawings on the walls. For check-ins, I asked everyone to share their “hope score,” with 5 being the most hopeful and 1 being the most despairing. There were some 5s and 1s, but the group probably averaged around 3.5 to 4. Not bad for Toronto, I thought.

I loosely base the structure of the event on

’s “Collective Presencing,” which, in my opinion, is the best “we-space” (also known as intersubjective meditation) practice. For the uninitiated, it’s like a Quaker-esque practice, where you speak when you feel called to. Very simple, but it often leads to profound conversations. However, when things become too intellectual, with many divergent views present, the discussion can get quite “schizo”—the online slang for perspectives converging too quickly, leading to no obvious coherence.I love it, though. I always love a collective schizo. After the event, Sofia and Dylan from

mentioned that they were surprised by how lightly I hold the conversational reins, with little intervention. However, there is a method to the seeming madness. Firstly, it should not be about me, or where I think the conversation should go, or my interpretation of what it means to “stay on topic.” Secondly, tracking the propositions that are verbally expressed is secondary; the main event happens in one’s body when holding all that is occurring (or wanting to occur) in the “social field,” the invisible dynamics happening among the social bodies present.Cheryl from “Collective Wholemaking” was also present, quietly holding the field. It’s not the easiest thing to do: you have to meet not only the emotions being expressed but also those being repressed, the ones loudly trying not to be noticed. You have to hold the social longing, the unconscious collective desire for something greater to emerge, while also bearing the silent tragedy of such potential not being realized—not yet, not now, but hopefully, one day.

It always feels so awkward in my body, but I am here for it. You need to have people who are here for it, trusting the inherent collective wisdom that is always present.

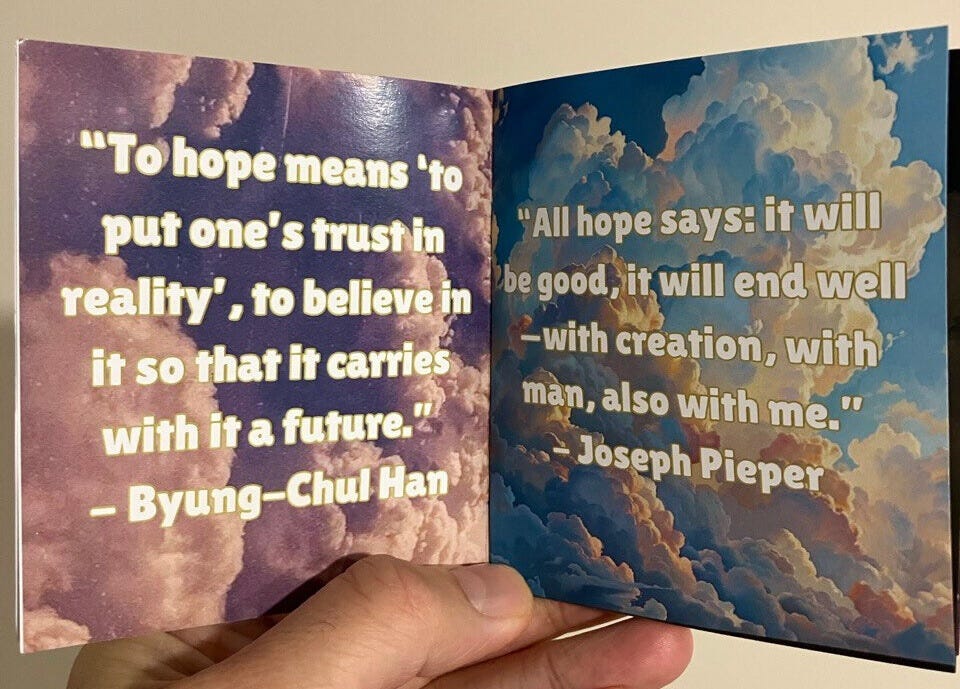

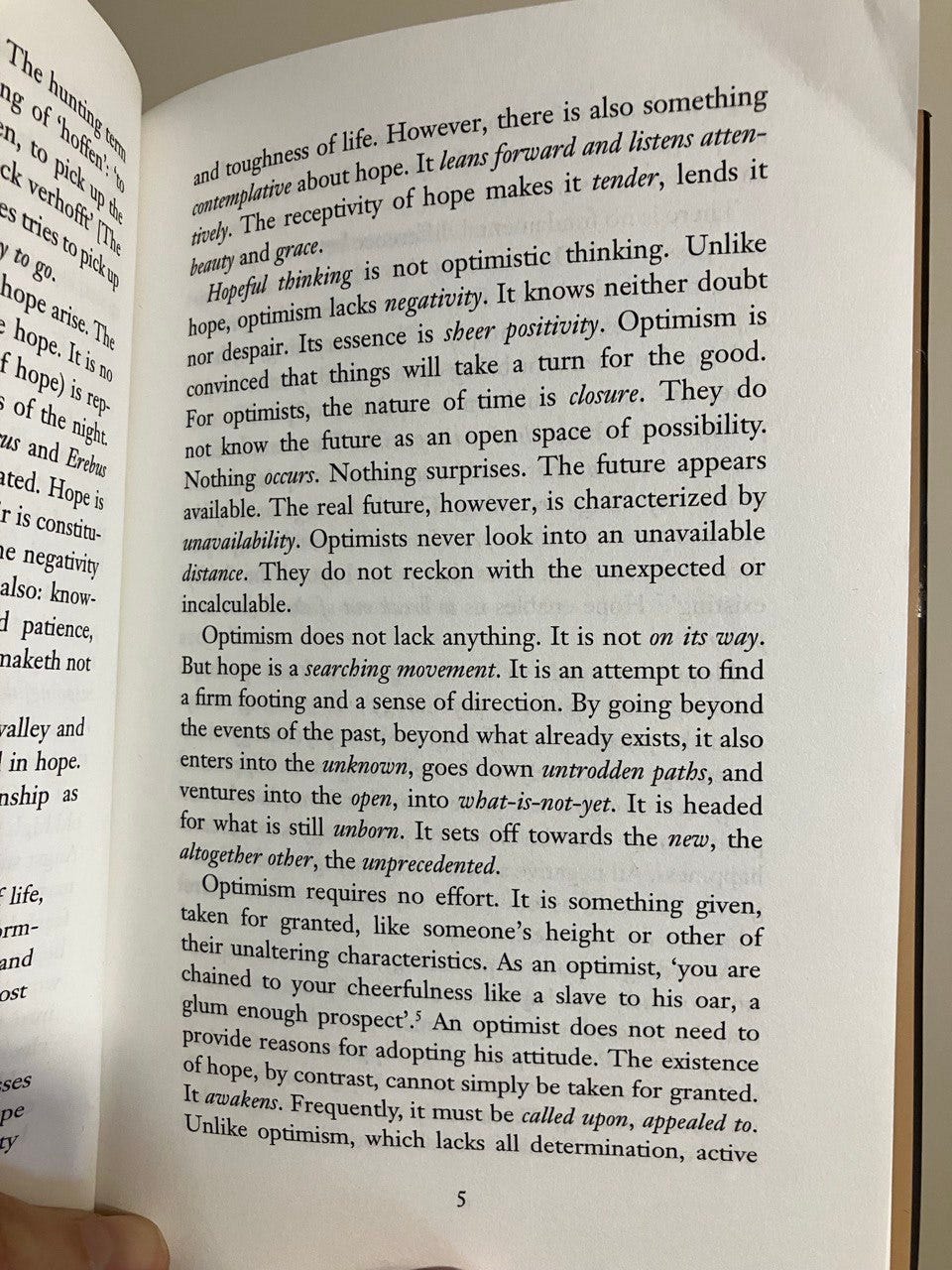

Things didn’t get too schizo, and people expressed that they had a wonderful time. It was a good, nourishing conversation with many interesting threads. One distinction discussed was between optimism and hope. According to philosopher Byung-Chul Han, whose book we read for the event, optimism should not be confused with hope. Optimism carries a certainty that a specific good will happen in the future, while hope lacks such certainty and remains open to possibility.

Category errors between optimism and hope occur frequently. The optimistic are often disappointed; they are too greedy for outcomes, doping themselves and others with the security of certainty. The opposite of hope, despair, is necessary to burn away the deadwood of optimism and give real hope a chance to emerge.

The thread that resonated most for me was mentioned by my friend John, who asked how hope is connected to love. This reminded me of what the biblical John wrote: God is love. I didn’t mention this to the group, but the moment in my life when I felt the most hope was when I first fell in love with my wife. Maybe we were just doped up on new relationship energy, but the world felt so open then, the possibilities expansive. I felt hopeful, with a heroic, punchy, “we can do anything” quality.

Love is the soil where hope sprouts. My barber's atheistic God-creation desire came to mind, and if St. John the Apostle’s premise is true, we do not need to wait for a superintelligence to tell us what to do. We only need access to the soil of hope. Of course, it’s hard to access this when so much remains unloved in the social fields we inhabit.

The conversational portion was coming to a close, and for checkouts, I asked the group to restate their hope score to see if any changes had occurred. Collectively, there was a mild improvement, though many said their score remained the same. I suspect everyone’s score actually did improve, but admitting it might have seemed uncool or as if we were forming a hope cult. The good news is that we didn’t gather to create another cult; we gathered to create a culture.

If you have any questions, insights, feedback, or criticism on this entry or more generally, message me below (I read and respond on Saturdays) …