Ten Core Techniques of Practical Philosophy

This entry is part of a series on practical philosophy: Part 1. Inquiring with Unknowing. Part 2: Practical Metaphilosophy. Part 3: Core Techniques.

This series is about the practical philosophy that helps guide my life. I felt called to write it so I could speak more clearly about it, especially since I’ll soon be on the Coaches Rising podcast. Its host,

, is specifically curious about what philosophical inquiry is.In the last entry, I wrote about the theory, or metaphilosophy, behind my practice and philosophical inquiry more generally. In this entry, I’ll be exploring the practice itself. I don’t have a formalized system; I’ve mostly been intuitively winging it since I began over four years ago.

That said, I do have techniques—lots of them.

The ones I’ll discuss today:

Socratic Ignorance

Socratic Questioning

Poetic Attunement

Tracing the X-Knot

Based Definitions

Concept Unfolding

Hegelian Dialectic

2x2fu

Forming Arguments

Theory Sketches

These ten techniques can be considered “philosophical.” They’re the ones I return to most often and form the core of my version of practically doing philosophy.

Ten Core Techniques

Some of these techniques were coined by me but can be found elsewhere, framed under different names, while others come from the “great philosophers” and modern thinkers. I’ll honour the original sources and then write briefly about the practice.

Socratic Ignorance

Source: Socrates and Plato

“I know that I know nothing.”

These are the famous words of Socrates.

Now, Socrates did know things, but this statement points to the state of unknowingness itself—what is called aporia.

Aporia is when you lose your sense of certainty in something. The way ahead becomes unclear; you stumble with your words, "break character," feel at a loss, and finally open to the mystery of what is and what could be.

No aporia, no philosophy.

Something else is happening if it's missing. That may be okay, even appropriate, but it’s no longer doing philosophy.

As the inquirer, I may have ideas about what is wise for my interlocutor. But if I mention these prematurely, I often overlook the complexity of the person I’m engaging with. As a result, the inquiry doesn’t land.

Hence, an aporetic holding on my part is needed throughout. I know that I know nothing. And together, we inquire through the aporia, honouring what we do not know and longing to know more.

Socratic Questioning

Source: Socrates and Plato

This one is simple: ask a question.

Then another.

And another.

Keep asking until your interlocutor and you reach the state of aporia.

Of course, the question should be related to the spirit of the inquiry. That is, it should be poetically attuned.

Poetic Attunement

Source: Steve March, drawing on Heidegger.

Drawing on the work of Martin Heidegger, Integral coach Steve March makes a distinction between “technological attunement” and “poetic attunement.” In the former, you treat reality as a resource to be used, focusing on what it can do for us. In the latter, you relate to reality as something to be with, open to what could happen together, in relationship.

For this to occur, Steve suggests we attune ourselves to the three transcendentals: the good, the true, and the beautiful.

From Steve:

You consciously attune your practice to the Love of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness for its own sake. Truth, Beauty, and Goodness are the three transcendentals as they were named by the Ancient Greek philosophers. This poetic way of attuning to experience creates one of the key conditions for unconcealing human virtues and unfolding the Truth, Beauty, and Goodness of you and your clients. The easiest way to engage this fundamental attunement is to generate a sincere curiosity about what’s true, to recognize the poetic beauty of what unfolds, and to appreciate the genuine goodness in yourself and in others, especially your coaching clients.

The good thing about this technique is that one does not need to have a strong theoretical understanding of each transcendental. They can simply sense it and attune themselves accordingly.

It leads to a poetic, flow-like inquiry, one that unfolds rather than being forced. It helps the inquirer make the subtle conversational moves that are, simply put, more beautiful. This technique is what makes inquiry an art, and it is especially fitting for philosophical inquiry.

Now, with the three fundamental dispositions—ignorance, the question, and attunement—we can begin to philosophize about what matters most for a person.

Tracing the X-knot

Source: R.D. Laing and Mary, Untier of Knots

An existential knot (x-knot) is the starting point of most of my inquiries. It is originally defined as:

An existential knot is an issue that feels deeply personal, most saliently experienced as a felt sense, and accompanied by great difficulty in coherently describing what the issue actually is. The person’s mental models are extremely entangled, with thought loops that lead to difficult emotions. When they try to “solve” the issue, they are met with disappointment and confusion. When they inquire into it on their own, they encounter frustration and a sense of stuckness. A common reaction is to escape into some form of coping. If the existential knot remains tied, an “existential crisis” follows.

I usually ask my interlocutor to start by describing something that feels bothersome—something existentially knotty. Sometimes it’s clear, but more often it’s not, and entering aporia tends to happen quite naturally when asked.

What I do next is trace the x-knot to find a thread loose enough to pull on. I inquire into four aspects:

The basic facts of the situation (and of their life more generally).

The emotions involved. I tease them to the surface just enough so I can feel them in my own body.

The beliefs about the situation, which usually involve their “story” of what’s happening.

The plans, if any, they have to resolve the situation.

The three most common x-knots in my practice are:

The untying begins once I understand (and feel) the contours of the knot.

Based Definitions

Source: Based Definitions: A Philosophical Practice

“Own your words, own your philosophy.”

The simple truth is: most people use borrowed words, or they treat their definition as the definition. This leads to talking past each other, silly debates, and culture warring.

To avoid this, it’s good to have a taxonomy of the types of definitions at play:

You can divide the understanding of definitions into two categories: content and origin. The latter is where borrowed and warring definitions are found. Lexical definitions (the borrowed ones) come from dictionaries or other “official” sources, while stipulative definitions (the warring ones) come from others' egos, insisting that everyone should adopt their definitions. I suggest a new kind of definition: based definitions.

Instead of relying on official sources, you check in with Source itself and come up with your own definitions—ones that are not only logically coherent but, more importantly, resonant with your body. Since these definitions come from someplace beyond the ego, you can hold them lightly, without putting pressure on others to adopt them.

In an inquiry, I pay close attention to the words being used and poetically attune to the ones that feel significant to the person’s x-knot. Often, a word will feel weighty in my body, as if it’s holding more than it needs to. I ask how they define that word. They pause, stumble a bit, and offer a muddled example instead of a clear definition. If they weren’t in aporia yet, they are now.

Sometimes we stay with a single word for the entire inquiry, working toward a tight and resonant definition. Other times, a provisional one is good enough—a first brick, so to speak, that helps lay the foundation for the rest of the inquiry.

Concept Unfolding

Source: Nicolas Benjamin, from his presentation at The Stoa.

A concept is a mental representation of reality that helps us understand it. Most people’s understanding of the world is built around concepts. For many, these concepts are borrowed, and most remain unexamined.

In truth, you can create your own. I do this all the time while writing on this Substack, and a few of them are discussed in this entry—such as existential knots and based definitions.

When wayfinding with another person, a concept is sometimes helpful for grasping a specific aspect of reality. Since a live inquiry isn’t conducive to scholarly research to verify whether a concept already exists—and because I don’t encourage unconscious intellectual servitude to public intellectuals or academics—I invite us to create one instead.

The term for this is “concept unfolding,” coined and introduced at The Stoa by my friend Nicolas Benjamin. While some people are naturally good at creating new concepts, Nicolas offered a particularly creative way to generate them on the fly.

As the one leading the philosophical inquiry, I either propose a new concept myself or help midwife one. Sometimes, when a concept emerges that is compelling, I suggest hosting a session at The Stoa to explore it further.

I did this with one of my ongoing conversational partners,

, and the concept he created: “ontological kindness,” which arose during our discussion about how to relate to others who hold worldviews in tension with our own.The rightly named concept can open up slices of reality to the mind that were previously hidden.

A personal example: When I was experiencing anxiety around the AI situation, I engaged in self-inquiry, and the concept of “AI-Realism” emerged—having a wise relationship with AI. This concept helped me see a north star beyond the foolish ways people were relating to it—either by unthinkingly using it or dismissing it in defeat.

When key words are defined, new concepts emerge, and a conversation between concepts begins.

Hegelian Dialectic

Source: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

The Hegelian dialectic unfolds through the following contradiction:

Thesis: The starting position

Antithesis: The counter-position

Synthesis: The resolutive position

The initial idea (thesis) meets its opposing challenge (antithesis), and from their tension arises a new truth (synthesis).

To use a concept mentioned above in dialectical form:

AI-Optimism: AI will save us!

AI-Pessimism: AI will destroy us!

AI-Realism: AI has great potential and great danger, and having a wise relationship with it means honouring both.

A synthesis is not a compromise or a simple middle ground. It is a higher-order, “meta” perspective that both preserves and transforms the previous terms.

2x2fu

Source: I believe this term was coined by Dave Chapman when referring to Venkatesh Rao’s prowess in creating 2x2s.

Another powerful tool that leads to philosophical clarity is creating a 2x2, affectionately called 2x2fu, as if it were a martial art for the practical philosopher.

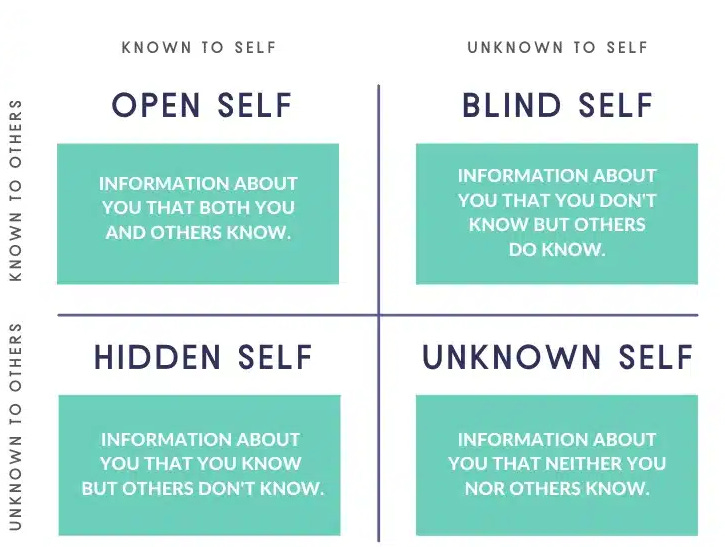

To create one, you need two axes, each with opposing extremes. A classic example of a 2x2 is the Johari Window:

On one axis, we have known to self and unknown to self; on the other, known to others and unknown to others. In each quadrant, a name is given that best fits—perhaps a concept you or someone else has previously unfolded.

You can also 2x2ify a dialectic. To use the AI one above...

The 2x2fu potential is endless. And like creating a new concept or dialectic, a good 2x2 can bring greater clarity.

Forming Arguments

Source: A term found in the field of informal logic.

An argument is a series of statements in which a conclusion (or contention) is supported by one or more premises.

Philosophical inquiries always form arguments.

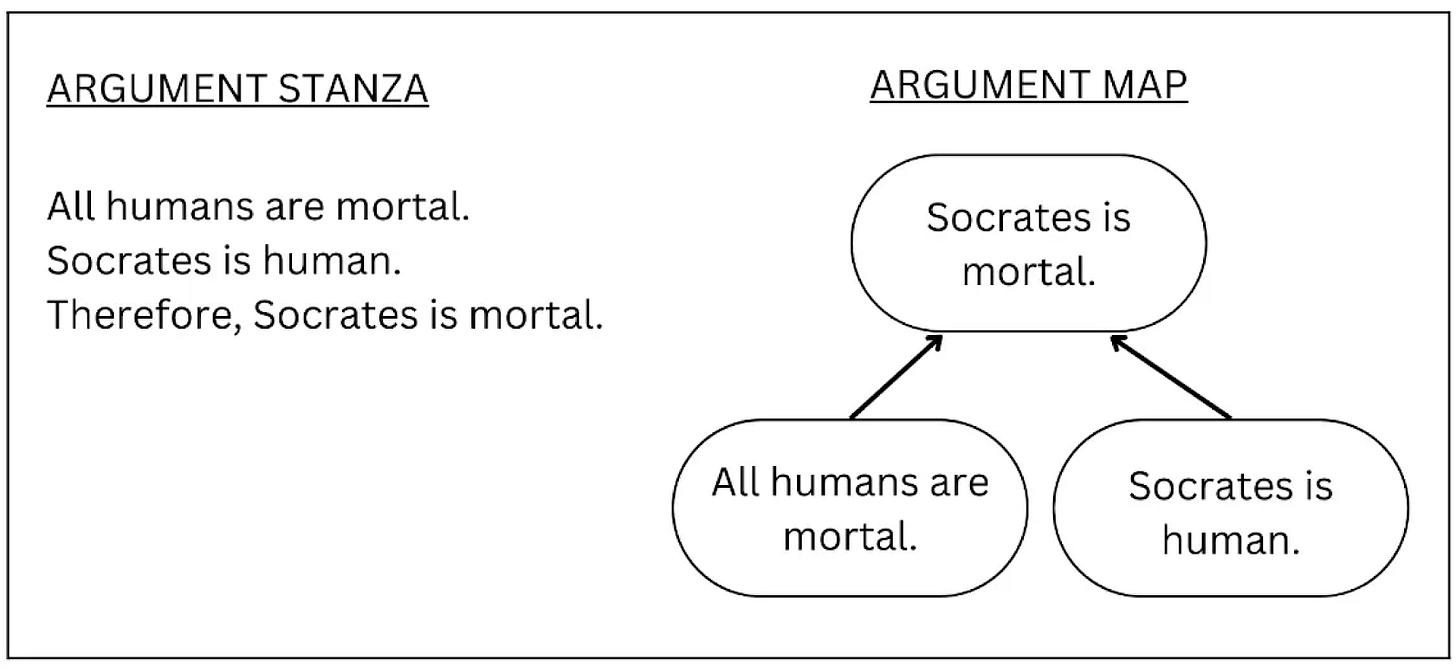

The standard argument form is a syllogism, where two premises support a conclusion. This can be expressed as an argument stanza or map. To use a classic example from introductory philosophy classes:

Formed arguments in the wild are usually polysyllogisms or complex arguments (multi-premised arguments). For example, to add some premises to the example above:

All humans are mortal. (Premise 1)

Socrates is human. (Premise 2)

Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (Conclusion 1, now Premise 3)

Whoever is mortal will die. (Premise 4)

Therefore, Socrates will die. (Conclusion 2)

To make the argument for AI-Realism, as mentioned above:

Powerful tools can help or harm us. (Premise 1)

AI is a powerful tool. (Premise 2)

Therefore, AI can help or harm us. (Conclusion 1, now Premise 3)

Wise use of tools honours both their benefits and harms. (Premise 4)

Therefore, a wise use of AI sees both its benefits and harms. (Conclusion 2)

There are other argument forms, such as hypothetical syllogisms, disjunctive syllogisms, and dilemmas. However, many arguments in the wild are known as enthymemes, which are arguments with suppressed premises—ones not clearly articulated but inferred by the audience—or proto-arguments, which are implied arguments whose stated premises do not clearly lead to the conclusion being argued for.

I am always tracking someone’s logical space and noticing their arguments form, but I rarely make them verbally explicit unless I am working with someone who has both the capacity and the need to see or hear them. Usually, this is a first-principles-thinking neurodivergent person.

I also make room for “poetic arguments.” One example comes from Gregory Bateson, known as his “Syllogism in Grass”:

Grass dies;

Men die;

Men are grass

The truth of poetic statements depends on them being false. They are not true in the narrow, classical logic sense, but rather in a holistic sense. This kind of truth is determined by one’s felt experience of resonance when reading with a disposition open to the whole.

When I first started my practice, my very first inquiry was with a wonderful artist named

. Thanks to his poetic disposition, our inquiries were full of poetic arguments, reminding me that philosophy does not live solely in the dry argument forms commonly found in academic papers.Theory Sketches

Source: “I Am Not Writing to the World: A Guide to Creating ‘Theory Sketches’”

If you have the following: clear definitions, new concepts, a dialectic, a 2x2, and good arguments, and if the inquiry is situated from an x-knot and some form of evidence exists, then you have the basis of a theory.

A theory is a systematic explanation aimed at understanding some aspect of reality. It includes definitions and concepts and shows the logical relationships between them.

The technique here is cultivating a theory with a certain disposition: non-attachment.

The theory, like any sketch, is throwawayable—something not taken too seriously, but at the same time, it could be the beginning of something more.

Moreover, the theory is for one’s wayfinding, not for an abstracted quest for truth as found in theoretical philosophy.

The vast majority of my inquiries do not result in finished theory sketches, but all inquiries begin with some form of sketching to allow greater clarity to emerge. Sometimes just a word is needed, a dialectic, or an argument or two.

Bonus: Option Space Mapping

Source: “The Creative Constraint of Knowing Your Option Space”

This bonus technique borders on philosophy and leans into coaching, therapeutic, or spiritual inquiry.

It involves mapping out one’s options in relation to their x-knot.

A perfect example of option space mapping appears in the song “3 Options” by Persian Empire.

The song uses audio of chef and restaurateur Marco Pierre White discussing his x-knot regarding vocational unhappiness and the options in front of him:

Option 1: Keep working 80–90 hours per week. Maintain status and income, but experience burnout and miss out on family life.

Option 2: Live a lie. Pretend he is still cooking while having others do the work. Maintain status and income, but compromise his integrity and risk being exposed.

Option 3: Quit. Give up his Michelin stars. Lose status and income, and embrace uncertainty.

Mapping out the option space is highly illuminating. It often involves dealing with difficult emotions (therapeutic inquiry), crafting clear strategies for action (coaching inquiry), or entering subtle realms to explore whether something unseen needs to shift (spiritual inquiry).

Toward a Whole Philosophy

A good philosophical inquiry should take you to the edge of philosophy. If one truly loves wisdom, they are bold enough to become one with it, rather than sheepishly loving it from a distance. At that point, philosophical inquiry ceases to be, and, hopefully, Wisdom begins.

A practical philosophy—of which my Less Foolish philosophy is an example—enjoys theory just as its counterpart, theoretical philosophy, does. However, its orientation is fundamentally different. The Good, rather than The True, is its central attractor. In addition, the subject matter is distinct: personal and situated, rather than abstract and general.

Lastly, all good philosophy eventually leads toward non-philosophy—not as an intended outcome, but as an emergent one. For practical philosophy, this unfolds as existential clarity that enables wise action; for theoretical philosophy, as conceptual clarity that enables wise thinking.

Of course, these boundaries are porous, and real philosophical inquiry often blends both theoretical and practical modes. There is also a third mode I gestured to above: poetic philosophy, oriented toward The Beautiful. Its subject matter is imaginal and felt, and its emergent outcome is aesthetic clarity that results in wise resonance.

All three modes are essential for a whole philosophy to re-emerge, and I believe the return of practical philosophy will help lead the way.

Come visit The Stoa for some practical, theortical, and poetic collective philosophy. Our keystone session, Collective Journaling, happens every weekday at 8 a.m. Eastern and is currently open to all.

Collective Journaling. Monday to Friday. @ 8:00 AM ET. RSVP here.

Also, we’ve got some epic one-off sessions coming up, all open to everyone:

AI Embodiment w/ Ari Kuschnir and Schuyler Brown. June 9th @ 12:00 PM ET. RSVP here.

Internet’s Dark Forests w/ Marta Ceccarelli. June 11th @ 12:00 PM ET. RSVP here.

iConscious: Accelerating Human Potential w/ Ted Strauss. July 7th @ 12:00 PM ET. RSVP here.

High Archetypal Penetrance w/ Tim Read. July 9th @ 12:00 PM ET. RSVP here.