Monasticization of Daily Life

This entry is a part of the “No Method: Practical Philosophical Skills” series. Part 1: Existential Wayfinding. Part 2: Weltanschauung Remodeling. Part 3: Monasticization of Daily Life.

In the book You Must Change Your Life, German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk argues we are practicing animals and sees philosophy as a “multisport,” an “exercise of existence,” with real philosophers being athletes of life.

Sloterdijk sees "five fronts" of existence that one must confront if they are to transform their life:

Material scarcity: our reliance on basic needs, such as food and water.

The burden character of existence: our being overtaxed from the vicissitudes of life.

Sexual drive: our sexual urges and the distresses they ensue.

Alienation: our "masters" (those who dominate us) and "enemies" (those who take from us) isolate us from others.

The involuntary nature of death: our evidential fate, "the terrorism of nature."

The philosopher-as-athlete confronts these givens of existence through self-transforming strategies of practice. Some strategies Sloterdijk references:

They fast so their appetites do not enslave them.

They outdo the “difficult through the even more difficult.”

They transmute excessive sexual desires toward spiritual motivations.

They submit themselves to a higher authority (a God) to not be beholden to temporal ones and have a “universal enemy within” (a devil) to overcome the compulsion for external enemies.

They create a “life-death continuum” through artful composure when “crossing over.”

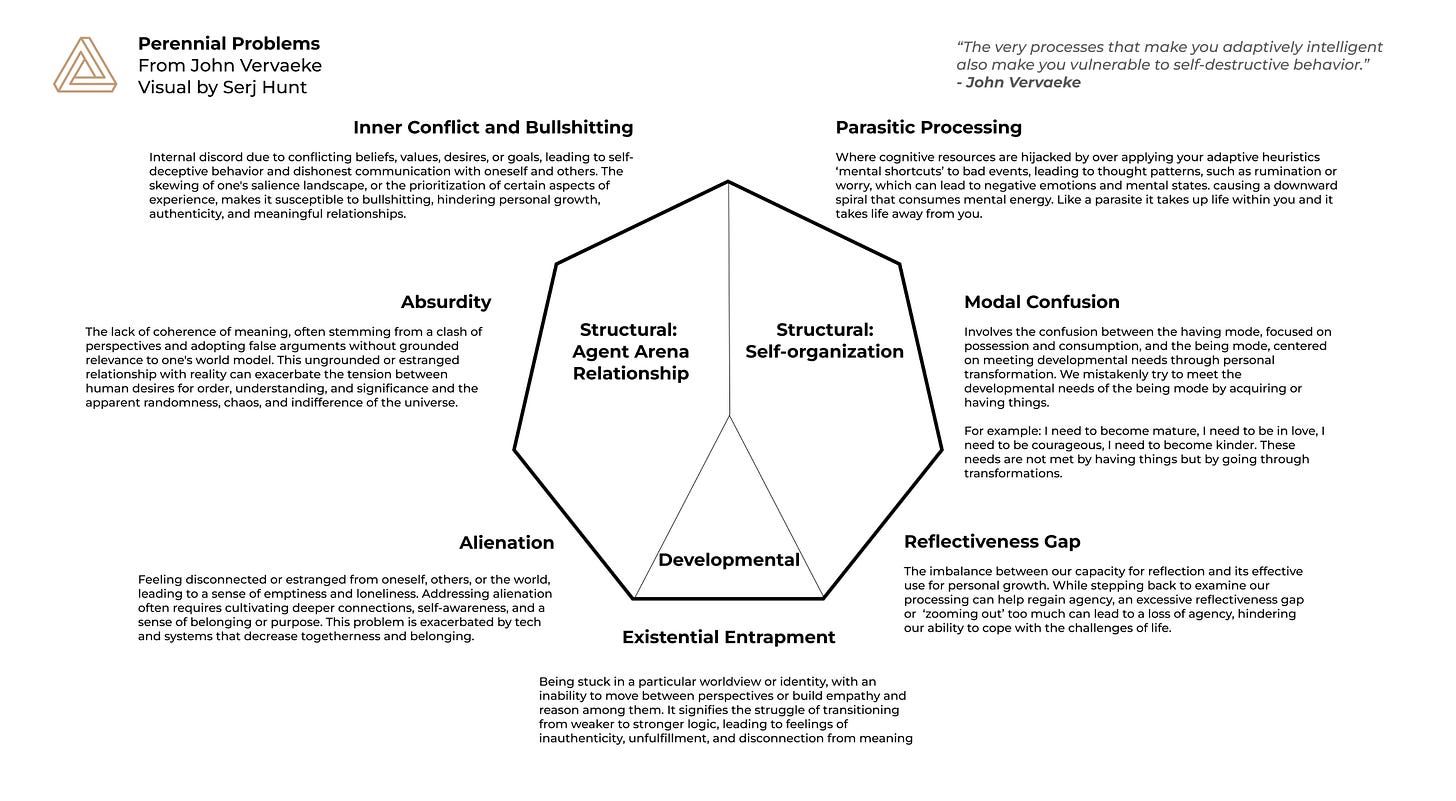

Like the five fronts, cognitive scientist John Vervaeke argues that humanity has wrestled with “perennial problems” since time immemorial. According to John, if we are to address our “wisdom famine,” our societal-wide lack of wisdom, we’ll need to be proactive in collectively responding to these problems.

The throughline between the five fronts and perennial problems is that humans are thrown into this world with “machinery” (our innately evolved processes) that leads to suffering. Sloterdijk and Vervaeke argue that practice, or an “ecology of practices,” is needed to live well and ameliorate our suffering.

We are always practicing something, and those living with “doxa,” aka common belief (or “normies”), have an ecology of unexamined practices that are not up to the task of living well. The reason for wisdom communities, such as monasteries, is for people to escape doxa and the ensuing unexamined practices by responding with a rigorous practice regime.

Monasteries are what sociologist Erving Goffman calls "total institutions," which he defines as "a place of residence and work where a large number of like-situated individuals, cut off from the wider society for an appreciable period of time, together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life." Total institutions shut down worldly distractions, blocking the memetic influence of doxa, and serving as an incubator for a transformed life.

The benefit of monastic living is that it is a focused container for an ecology of practices that addresses the five fronts and perennial problems. While the popular image of monastic life is that monastics engage in advanced meditation or prayer, the less glamorous practices are just as important—waking up consistently at the same time, cleaning, having a schedule, etc.

In my philosophical inquiries, what is often needed is not some fancy wayfinding or a rehauling of one's philosophy but a recommendation of a simple practice: getting better quality sleep, exercising and eating well, or engaging in the best practices of being agentic, such as Getting Things Done, Building a Second Brain, time blocking, and having a power down ritual.

The affordances of monastic living, thanks to the communal pressure toward becoming excellent at life, allow many of these basic practices to emerge with little consideration. Any advanced practice regime will only occur with them. Most of us who live outside of total institutions struggle with the basics. Our capitalistic system is designed to profit from our lack of agency and people's agency directed toward non-sacred pursuits.

What is the solution for those whose calling exists outside of a monastery? Consider the world your monastery. I first heard the phrase "monasticization of daily life" from the Coaches Rising podcast, and it resonated immediately. All life is practice, and the monasticization of daily life is the art of flipping unexamined practices into examined ones.

The challenge with non-monastic living is each person's ecology of practices needs to be bespoke to them. A person cannot simply adopt a complete practice regime to live life. We all have different health needs, personal challenges, living conditions, professions, and callings, that require practices fitted for each person's life.

To gain a greater practice consciousness, I recommend selecting a "generator practice." This practice should ripple out consciousness, promoting other practices to be consciously adopted and done with a hard commitment. It could be working out, meditating, breathwork, or my personal favorite: philosophical inquiry, whether in a journal with oneself or with a friend of virtue.

Philosophical inquiry is the practice that allows awareness of all other practices, making an ecology of practices conscious of itself. It does this by honing in on a bothersome, unexamined issue, wrapping attention around it, and becoming intimate with its contours. What results is often practical, like a practice being introduced or reconsidered.

For those reading now who feel unsatisfied with their ecology of practices and who are practicing "bad habits," here is an exercise that will start your journey toward the monasticization of daily life:

Block 30-60 minutes in your schedule for a journal exercise to answer the following question: What is your "generator practice"?

This practice is the highest leverage practice you can start now.

This practice will most likely be simple: waking up at 6 AM daily, meditation for 30 minutes, or Collective Journalling at The Stoa 🥰.

Commit to "no zero days" - a disposition of no compromise - for a set number of days, e.g., seven days.

After you decide on your generator practice, write down the entirety of your aspirational ecology of practices.

These will be practices that you can start now. Have above 70% "credence level" - your belief in percentage - that you can do them all.

To avoid any "shame spiraling" - a sense of not good enoughness - do not adopt the mindset that all your practices must be complete. Instead, approach them with curiosity as to why they did or did not get done. Having an inquiry practice is suitable for such an examination.

Have a place to track them. Do the tracking with a pen and paper or one of the many existing habit-tracking apps. Sebastian Marshall's "Lights Spreadsheet" is a tracker I recommend.

Call upon a friend of virtue - someone oriented toward your highest self and you to theirs - and have them keep you accountable for the duration of this exercise. Engage in philosophical inquiry with them about what came up for you after finishing the exercise.

While the etymology of the word monastery is "to live alone," no monastery exists without others. It is an altogether social experience. Finding virtuous others will be needed to turn the world into a monastery.

***

To conclude this series on practical philosophical skills, I will make a prediction: philosophical inquiry will be the generator practice for friendships of virtue to emerge. No other modality simultaneously allows somatic, practical, and theoretical intimacy.

It never felt right to situate my practice in the market economy, with the gift economy being a better fit. My philosophy practice was essentially being a surrogate for a friend of virtue. Friends of virtue require tremendous intimacy and commitment and must be able to help their friends find their way, remodel their worldviews, and turn their world into a monastery.

I want to see a world where these kinds of friends are common, with a culture supporting them. In upcoming entries, I will provide practices to establish a friend of virtue culture pointed toward becoming less foolish.