In the Internet Real Life series with

, we are engaging in the following dialectic:Internet-optimism: Yay, the internet is amazing—utopia, here we come!

Internet-pessimism: Actually, the internet is not so great and has led us to a dystopia.

Internet-realism: Hmm, the internet can be bad, but maybe we can develop a wiser relationship with it.

It has been a rewarding series, and we are collectively discovering what “internet-realism” could be. I’m currently reading a book that is helping me sense my way toward an answer—The Spirit of Hope by “the internet’s favorite philosopher,” Byung-Chul Han.

The book begins by discussing optimism and pessimism, and what these positions have in common. Regarding optimism, Han writes:

Hopeful thinking is not optimistic thinking. Unlike hope, optimism lacks negativity. It knows neither doubt nor despair. Its essence is sheer positivity. Optimism is convinced that things will take a turn for the good. For optimists, the nature of time is closure. They do not know the future as an open space of possibility. Nothing occurs. Nothing surprises. The future appears available. The real future, however, is characterized by unavailability. Optimists never look into an unavailable distance. They do not reckon with the unexpected or incalculable.

He argues that there is “no fundamental difference between optimism and pessimism” and that “one mirrors the other.” Regarding pessimism, he continues:

For the pessimist, time is also closed. Pessimists are locked in “time as prison.” Pessimists simply reject everything, without striving for renewal or being open towards possible worlds. They are just as stubborn as optimists. Optimists and pessimists are both blind to the possible. They cannot conceive of an event that would constitute a surprising twist to the way things are going. They lack imagination of the new and passion for the unprecedented. Those who hope put their trust in possibilities that point beyond the “badly existing.” Hope enables us to break out of closed time as a prison.

Hope sets us free, puts us on an adventure, and brings us into intimacy with the unknown. Yes, things are bad, but we sense they can get better. We do not know how or why, because we submit to the mystery—the uncontrollability of the world—and become surprised, opened to the possibility of something truly new emerging. The problem with both optimists and pessimists is that they are far too certain and arrogant about the world’s problems and the solutions it needs.

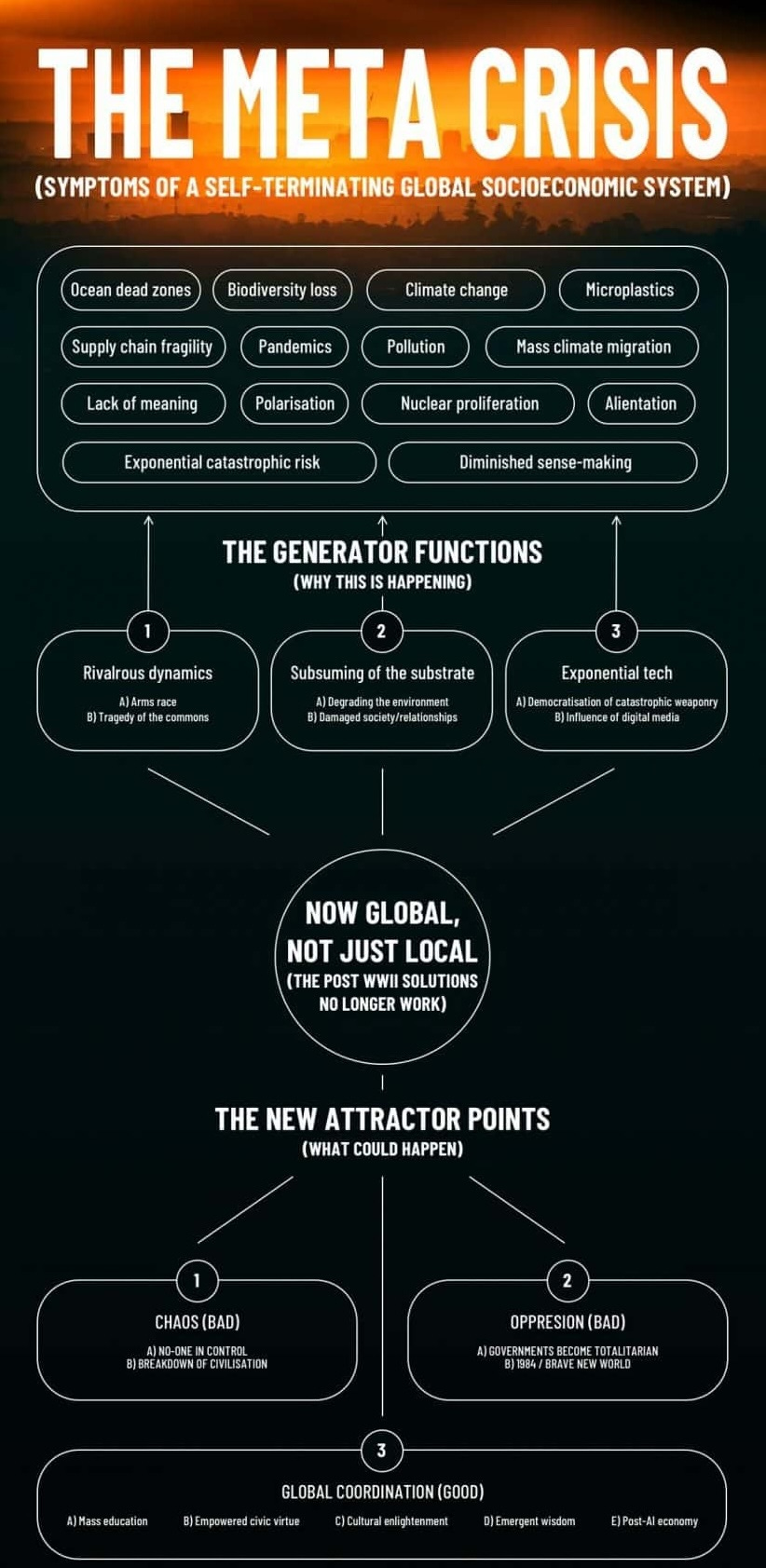

Currently, pessimism is winning out, and as Han notes, we face multiple crises that paint a bleak picture. Since 2020, we have been exploring the intersection of crises at The Stoa, which the power elite call the “polycrisis” and we have termed the “metacrisis”—the better model of the two, as the former tacitly promotes top-down control, while the latter aims for bottom-up agency. While I have personally moved away from the metacrisis framing, it still captures many aspects of our collective predicament. Here is a comprehensive infographic:

It’s probably a good sensemaking rite of passage to go through a metacrisis phase, but such modeling has an alien quality. It is too darkly meta, lacking poetry, and unlikely to resonate with anyone beyond those inclined toward excessive abstraction. It also leads to doomer fetishism when no corresponding hope is emphasized. Most importantly, it offers no practical or spiritual guidance for the individual.

Even if the metacrisis may be the best model that reason can offer, reason can only take us so far. Hope is needed where reason fails, as Han asserts:

However, hope builds a bridge across the abyss into which reason cannot look. It can hear an undertone to which reason is deaf. Reason does not recognize the signs of what is coming, what is not yet born. Reason is an organ that detects what is already there.

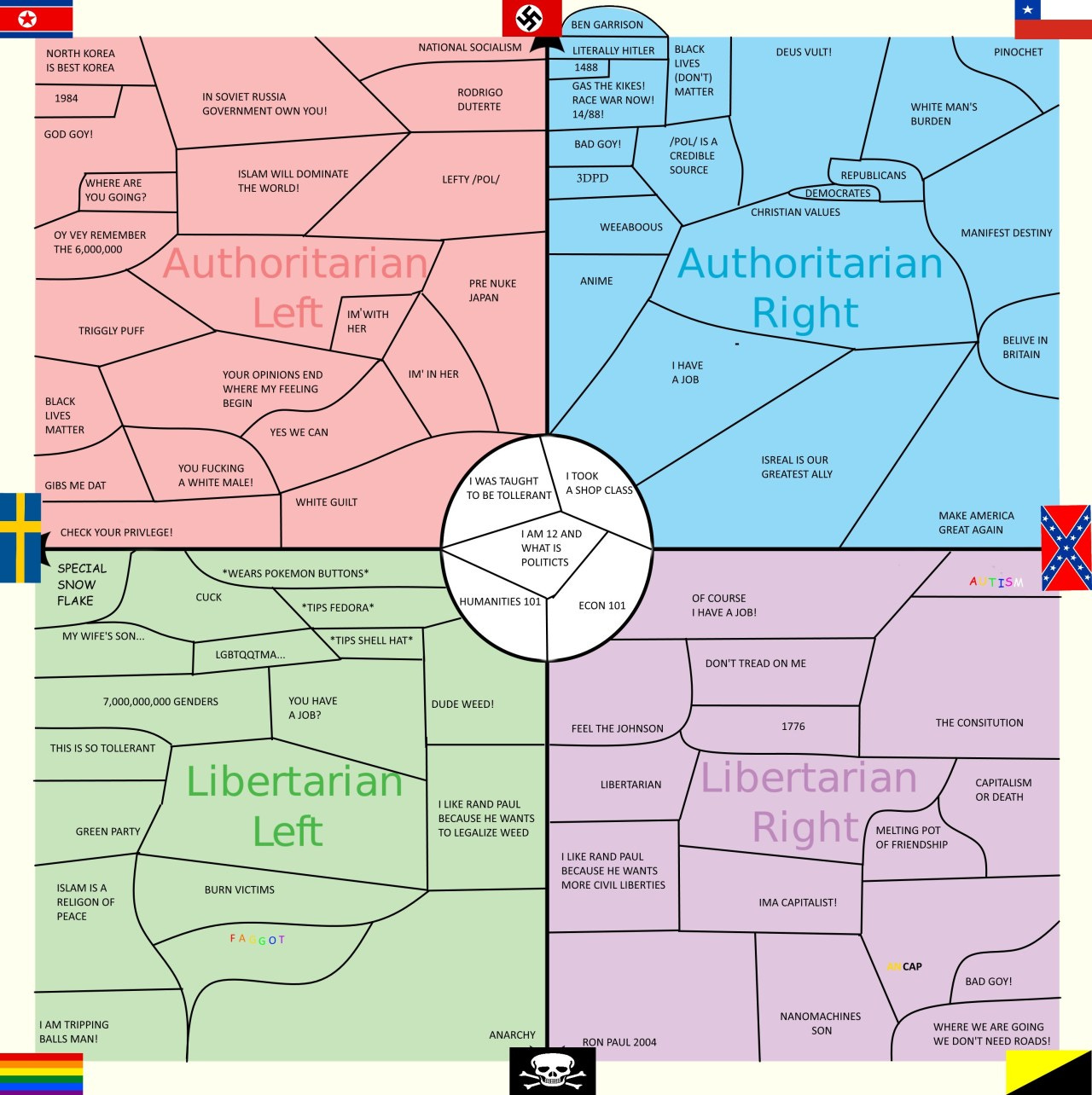

Hope is deeply spiritual. It is spiritual sight—a profound sensory mechanism that opens up the future, unlike a mind fueled by fear, which closes it down by attempting to control it. I fully support Han’s advocacy for a “politics of hope.” However, I am not convinced that those who consider themselves political and reasonably rely on political compasses—which only “detect what is already there”—will navigate our present situation with wisdom.

Firstly, I doubt that any of the political ideologies represented by the quadrants offers a good response to what the metacrisis model points toward. Secondly, many people who are too invested in politics, whether left or right, not only grapple with archetypal mommy and daddy issues but are also haunted by a hopeless pessimism. This is to say, they are too certain and intellectually arrogant. True hopefulness, by contrast, lacks such certainty and embodies intellectual humility.

The last time hope was used in politics was during Barack Obama’s first campaign, which was brilliantly executed and tapped into something many felt was deeply hopeful. Millennials first became political during the Obama era, experiencing this sense of hopefulness, and many have been trying to recapture it ever since, with Kamala Harris’ “Brat Summer” as their last, joyously desperate attempt. However, none of this was real hope as Han understands it. It was what came to be known as “hopium”—an intoxication with the promise of hope.

I am now skeptical that real hope can be tethered to a political agenda guided by a political compass, regardless of how reasonable it may seem. Hope is not optimism or pessimism, nor is it hopium. It is something else—a surprise, an adventure, a realism that acknowledges our reasoning cannot control the fate of the world.

If you have any questions, insights, feedback, or criticism on this entry or more generally, message me below (I read and respond on Saturdays) …