"A modern philosopher who has never once suspected himself of being a charlatan must be such a shallow mind that his work is probably not worth reading."

- Leszek Kolakowski, Metaphysical Horror

People who get into philosophy can be insufferable and then tend to suffer if they allow philosophy to affect [infect] their lives, as philosophizing can be a treadmill that never ends. I would not recommend studying it because then you must learn how to escape it.

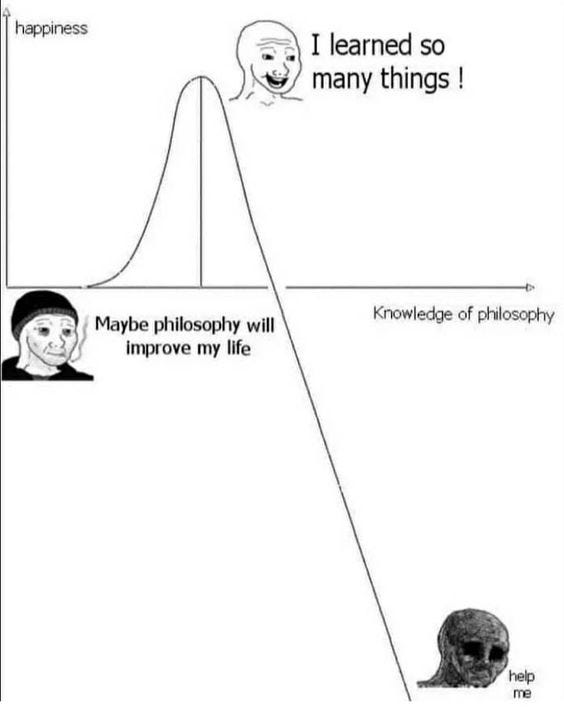

The journey of the "philosopher" is not a glamorous one. It goes something like this:

Firstly, when one starts getting into philosophy, they discover many ideas challenging their basic assumptions. This discovery initially invokes feelings of superiority, and they begin to carry the following attitude into every conversation: "Hah, I am not like those normies hopelessly guided by unexamined ideas!" It is as if reading a few chapters of Nietzsche has brought them one step closer to becoming the Übermensch.

In retrospect, the "philosopher’s" fondest memory of philosophizing is with friends in cafes and bars outside of schooling or philosophical readings. They misattribute this enjoyment to enjoying philosophizing when what they really enjoyed was socializing with stimulants and depressants during their youth, a phase when the horizon of possibilities felt endless.

The “philosopher” believes they are a courageous truth-seeker, unflinchingly chartering mental territory no normie has gone before. In reality, their main drive stems from seeking a "narcissistic supply"1 in the feeling of superiority they get by steering conversations into uncomfortable territories that push others to the edge of their thinking. This motivation results in finding any conversational opening to turn "shallow" conversations into "deep" ones.

Soon, the sense of superiority becomes addictive, motivating them further to learn philosophy, putting their non-philosophical interlocutors at a conversational disadvantage. Indulging in power trips becomes habitual, seeking more social opportunities to challenge someone's unexamined source of meaning.

These power trips are socially obnoxious and can be quite cruel. While the "philosopher" assumes they bravely think like Socrates, nobly gadflying others into the examined life, their unconscious motivation leads them to attempt to undermine others' worldviews, potentially untethering them from their sanity.

Understandably, this isolates the "philosopher" from normal people with normal interests and responsibilities. This isolation leads to a social circle comprised of other pretentious "philosophers" who are unbearable to be around, ultimately resulting in complete social alienation.

At this stage, so much philosophizing has been done that the "law of the instrument"2 is in full effect: any personal problem can only be addressed through more philosophizing.

The point of no return has been crossed. With an absence of meaningful social connections and a poverty of practical life skills, the “philosopher” sees no choice but to go all the way, discovering the real “telos”3 of philosophy: the disenchantment with philosophy.

A full-blown disenchantment with philosophy brings the painful realization that philosophy cannot solve their problems and does more harm than good. Philosopher Giambattista Vico's expression of the "barbarism of reflection" is appropriate here: a historical phase where over-intellectualization and excessive reliance on reason leads to cultural decay, tearing down "irrational" norms, customs, and religions. This "barbarism" is not toward other bodies but toward other minds.

Feeling into their past barbarism, the "philosopher" turns a critical eye to philosophy itself and all the philosophers in the Western canon. They question why certain philosophers, such as Vico, remain largely overlooked while others, like Nietzsche, are revered as indisputably brilliant. They skeptically consider that factors like unwitting promotional strategies might play a more prominent role in these philosophers' renown than the actual value of their ideas.

With disillusionment toward people who symbolically represent philosophy, their philosophical heroes appear to be charlatans, bamboozling others with copious amounts of words. In truth, there is no clear evidence their “love of wisdom” resulted in a life worthy of admiration.

Once the idolization ends, a surprising sense of relief occurs with the following realization: nobody really knows shit. A thought begins to surface: "If even these highly impressive galaxy-brained philosophers can't guide me on how to live my life, maybe I shouldn't be so hard on myself for not having all the answers on how to live mine."

Socrates' declaration that he knows that he knows nothing no longer becomes a cute party line one larps for narcissistic supply; it now is an embodied truth. The "philosopher" realizes they have been a fool all along. At this stage, they may consider what is beyond philosophy, appreciating the beauty and seeing the "lindy"4 aspect of religion, realizing that these traditions survived as long as they did for good reasons.

A non-philosophical answer allows the barbarism of reflection to stop finally, bringing greater peace to the "philosopher's" body.

***

The journey outlined above is part anthropological observation and part projection. Not all "philosophers" go down this path; some become professional philosophers, aka "sophists," finding a career in academia. This choice prevents them from reaching the other side because institutional incentives neuter the spirit of philosophy.

“It’s a clichéd observation that we professional philosophers are, in Socrates’ terms, sophists. We may profess to love wisdom, and be ever so sincere in claiming as much, but we’re still getting paid—even if not quite so much as we should be.”

- Liam Kofi Bright, Why I’m a Shameless Sophist

Despite my criticisms of our "philosopher," I hold that doing philosophy, or philosophical inquiry, is essential today. However, it should be freed from unexamined motivational patterns and professionalization. Philosophy must be firmly rooted in genuine "aporia"5 and a commitment to becoming less foolish.

If Oprah magazine6 serves as a barometer of cultural mainstreaming, philosophical counseling is on the rise. It will surpass coaching and therapy in popularity, as the clarity of wisdom not only can facilitate worldly achievements and emotional catharsis but also offers liberation from the barbaric internal chatter of one's mind.

If you have any questions, insights, feedback, or criticism on this entry or more generally, message me below (I read and respond on Saturdays) …

Narcissistic supply is the source of what makes someone feel special, which could be their looks, status, talent, or philosophical sophistication.

The law of the instrument (also known as Maslow’s hammer or the golden hammer), often summarized by the phrase "to a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail," is a cognitive bias that involves an over-reliance on a familiar tool or method, ignoring or undervaluing alternative approaches.

The lindy effect is the notion that the future life expectancy of something is proportional to their current age, suggesting that the longer something has survived, the longer it is likely to continue to survive.

“This Therapy Is Like a Personal Trainer for Your Mind—and Your Soul” by Jennifer King Lindley, Oprah Magazine