Scene Review: CCCRU (Most Based)

Sensemaking—the process of understanding the world to navigate within it—was a common phrase in the niche online scenes I was part of. I appreciate the phrase because making sense of the world requires relying on all your senses to discern, not just your mind or the minds of others.

As some foresaw,1 sensemakers will replace influencers as trust in legacy media declines, ambient anxiety builds amid social media’s relentless memetic noise, and the parasocial weirdness of online life becomes increasingly apparent. There’s a growing desire to understand and interpret the world in new ways, alongside new people. From the sensemakers I followed, the message was clear: step away from the screen and create a scene.

There’s only so much sensemaking you can do online before realizing it leads to scenemaking. Sensemaking can only take us so far in understanding the world; eventually, we must transition to scenemaking to begin shaping it—through culture. Having accurate models of reality and refined political ideologies is valuable, but ultimately, culture yields to good art.

Often seen as communities centered around a specific art form, scenes play a crucial role in shaping broader culture—think of the Beats or the Punks. Alternatively, scenes can be understood through what Brian Eno calls “scenius,” a concept that Kevin Kelly describes as communal genius.

“Individuals immersed in a productive scenius will blossom and produce their best work. When buoyed by scenius, you act like genius. Your like-minded peers, and the entire environment inspire you.” - Kevin Kelly, “Scenius, or Communal Genius”

Bringing The Stoa’s online scene more fully to Toronto has been on my to-do list, but for various reasons, I haven’t felt called to do it—partly because I’m aware of the significant effort required to steward a scene. However, I was pleasantly surprised to discover the emergence of a new scene in Toronto: the CCCRU (Canadian Cybernetic Culture Research Unit).

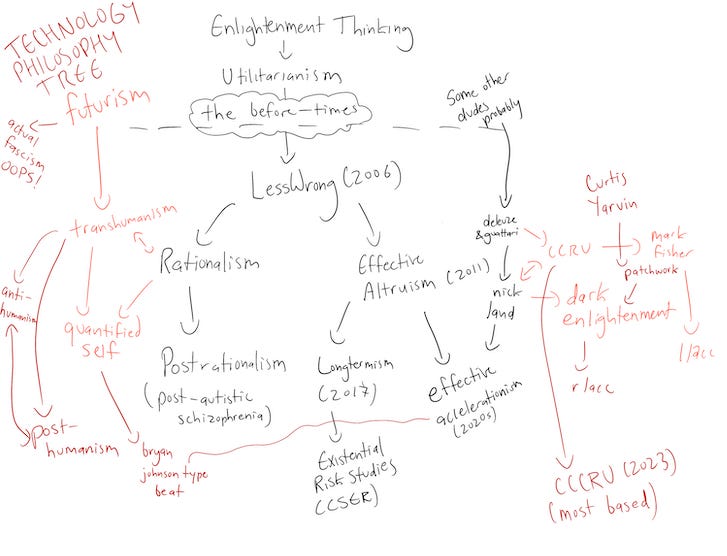

The group’s name is a play on the original CCRU, established in 1995 at Warwick University with philosophers like Nick Land and the late Mark Fisher. I recently met with one of the CCCRU leaders, who shared with me a schizo-sketch of how he views this burgeoning scene as part of the larger memetic landscape.

CCCRU—the most based—operates from a clandestine studio in Toronto, where a group of avant-garde creators focuses on political and cultural commentary. Members include Jreg, Art Chad, Hallie Tut, We’re in Hell, Duncan Clarke, Gokanaru, Ben from Canada, 1Dime, Saplow, and Jane Gatsby, a former guest at The Stoa.

Others who shape the scene include Oki’s Weird Stories, CJ the X, Maya Ben, and any content creators visiting the studio in Toronto, such as Hegelian e-girls.

As Joshua Citarella highlights in a recent piece on the CCCRU,2 they are a politically diverse group that defies being pigeonholed into a single ideology—which is incredibly refreshing. Instead of what passed for political engagement in previous years—culture warring, canceling, and virtue signaling—CCCRU brings together people from opposing political positions who create and party alongside one another, united primarily by their interest in political theory and online creation.

“The CCCRU is a video art collective for the 21st century. It’s an inspiring group show with real independence and creative freedom. This should give us all some hope for the future.” - Joshua Citarella, “The Real Horseshoe Theory”

This newfound political freedom could be generational or a result of fatigue with the culture war, but I also think the steward of the scene, Jreg (Greg Guevara), holds a piece of the puzzle. Jreg creates content that satirically tackles various political ideologies through ironic humor, blending comedy, commentary, and critique to explore political issues while blurring the lines between parody and serious discourse.

In essence, when watching Jreg’s videos, you are not meant to walk away with certainty about his political positions. Maybe he’s a democratic socialist siphoning the countercultural edginess of the dissident right, or perhaps he’s secretly a ghost-skinned hyperborean Identitarian going deep undercover among the BreadTubers. He could also just be “schizo,” a mirror reflecting our capitalism-induced schizophrenia, with his art as an act of “deterritorialization.”3

In any case, when I hung out with him, none of that mattered. After getting a sense of him, I knew he was a good guy trying to make sense of the world with his fellow scenemaking homies. That said, I do see some truth in the “schizo” interpretation—when someone operates at their creative edge, using ideologies as their art, transperspectival alchemy abounds.

Through the lens of developmental psychologist Robert Kegan, Jreg and the CCCRU are building a cultural bridge between the “self-authoring mind” and the “self-transforming mind.” This transition marks a shift from individuals who define their own beliefs and values to those who can hold multiple perspectives simultaneously, integrating them into a more complex understanding of the whole.

While the self-authoring mind takes ownership of its ideology, striving to make it the core of its identity, it ultimately becomes part of the “art” created by those with self-transforming minds. The internet has seen a boom in political self-authoring, with ideologies-of-one emerging daily—excellently tracked by Citarella in Politigram and the Post-left, one of Jreg’s early influences.

While creating such “e-deologies”4 may offer a sense of agency, they prove politically ineffective in practice. I'm not wagering on culture being shaped by niche ideologies crafted by extremely online individuals. Instead, I’m betting on scenes—especially self-transforming ones—where people create art, not propaganda, together, sensing what new cultures will emerge.

“I would entrust art with the task of developing a new way of life, a new awareness, a new narrative against the prevailing doctrine. As such, the saviour is not philosophy but art. Or I practise philosophy as art.” - Byung-Chul Han, “I Practise Philosophy as Art”

The emergence of post-internet scenes such as San Francisco’s TPOT, New York’s Dime Square, and now Toronto’s CCCRU sits at the edges of our culture. The latter blends online sensemaking with IRL scenemaking, giving new cultures a chance to emerge.

If Kegan’s framing is appropriate here, and post-internet scenes are oriented toward “self-transforming minds”—where propositional contradictions can be held and a dialectic between ideologies can occur—then they may serve as incubators for something truly unpredictable and surprising to emerge.

Besides, culture isn’t meant to be based on clearly articulable propositions sourced from one person—that’s a cult, an anticulture. Instead, culture emerges from sensing something beyond the propositional, driven by a creative force that, when listened to, tends to bring people together.

“Overwhelmed by the sheer volume of conflicting information, hot takes, scoldcore, and didactic thinkpieces from the Professional Managerial Class, people increasingly trust only those to whom they’re directly connected—whether personally, or parasocially. And this is why non-institutional figures—Substack writers, artists, podcasters—and their wider communities will continue to fulfill the role of Trusted Sensemakers. Meanwhile, corporations and governments will need to cultivate relationships with these sensemakers in order to gain broader trust—and traction.” - Caroline Busta and LIL INTERNET, “Holographic Media”

Coined by Deleuze and Guattari, deterritorialization refers to the process of disassociating or breaking down the boundaries and structures that define a particular "territory," whether it be physical, social, cultural, or ideological, allowing for the emergence of new forms and connections.

“E-deology is an internet slang term used to describe complex ideological labels. These hyper-specific categories serve as a gamified form of identity play and niche personal branding in the chaotic landscape of online politics.” - Joshua Citarella, “e-deologies V, 2023”