Camille and I had a very touching, beautiful experience last weekend related to our emerging faith, but it's all very personal, not something I want to discuss much here, as one should not sensationalize their spiritual experiences.

Since September of last year, we’ve identified as Christian. When we were young, we were baptized in the Church (I was baptized Orthodox, she Catholic), but we never attended. Now we are returning and learning: going to church, reading the Bible, taking an Alpha course, and so on.

On another front, since 2002, over two decades ago, I’ve experienced what I call a “philosophical opening,” a period when I began questioning everything, including philosophy itself. I found myself rebelling against the gatekeepers of philosophy and how they understood it, which was largely theoretical and confined to the university. Instead, I was most attracted to the spirit of philosophy, the love of wisdom, which I believe is most readily expressed in practical philosophy rather than its theoretical counterpart.

In my non-Christian days, doing philosophy seemed to guide me, but in reality, it didn’t offer true guidance. Instead, it left me in a state of perplexity, stripping away false certainty and, over time, clearing out philosophical deadwood to make things slightly clearer. In essence, it helped me shed unnecessary, assumption-laden clutter—ideas borrowed from others without question.

Still, I put too much pressure on philosophy to be something it was never meant to be. I was spiritually stubborn, and I did not want to take a knee. In essence, I made an idol out of philosophy.

I recently finished outlining my framework for how I understand and, more importantly, practice philosophy. However, I wrote it primarily through a secular lens, lacking the spiritual richness of my emerging faith. I did my best to make the framework internally coherent, but on its own, it is incomplete and risks conveying that doing philosophy is all you need for the good life.

It’s not.

Philosophy cannot serve itself. It is the love of wisdom, not Wisdom itself. It is, then, as they say, a handmaiden to something else.

But what?

Some well-known phrases already exist:

Philosophy is the handmaiden of theology.

Philosophy is the handmaiden of science.

I’d add a third, which, in practice, is gaining in popularity:

Philosophy is the handmaiden of ego.

It could also, theoretically, be a handmaiden to something else—nature, life itself, “entities,” or even careerism for academic philosophers.

However, the above choices—theology, science, and ego—are the main contenders today. I’ll go through each.

Philosophy Is the Handmaiden of Theology

Thomas Aquinas—friar, priest, philosopher, and theologian—advocated for philosophia ancilla theologiae: philosophy having a supportive relationship to theology.

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains:

“Philosophy and theology form a coherent, mutually supportive whole. They are not in conflict with respect to their conclusions, since truth cannot contradict truth, but they differ with respect to their foundational axioms, goals, and sources of evidence. Philosophy is understood as a preamble to theology, while theology completes and fulfills philosophy.” - Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Theology is the study of God and His revealed truth. It is both descriptive and prescriptive. According to Aquinas, theology is the higher “science,” or scientia, because it comes from divine revelation rather than from the human mind. Philosophical reasoning is still important for clarifying and articulating revelation, as well as for resolving potential confusions.

Another phrase from Anselm of Canterbury, Credo ut intelligam (“I believe so that I may understand”), captures the handmaiden disposition well. Belief is not the end of inquiry—or if it is, then it is the end of a foolish kind. Rather, belief is the beginning of a true inquiry, where philosophy, knowing its place, affords deeper reflection.

Yet modern atheistic minds are unsatisfied with this relational placement of philosophy and see it under different leadership.

Philosophy Is the Handmaiden of Science

The New Atheist movement was most popular around 2007, led by Richard Dawkins and the other “Four Horsemen”: Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens, and Daniel Dennett, along with science communicators like Neil deGrasse Tyson. New Atheists tend to be humanists in ethics, materialists in metaphysics, and skeptics in epistemology. Their worldview generally consists of the following premises:

Religion, such as Christianity, is false.

Religion, especially Islam, is harmful.

Morality can exist without religion.

Science is the primary method for discovering truth.

Philosophy, then, should play a subservient role to science and to whatever presently represents scientific consensus. The phrase, sometimes attributed to the English philosopher John Locke, is not as widely known as its philosophia ancilla theologiae counterpart, but it is deeply embedded in New Atheist thinking. Its proponents tend to view philosophy’s handmaiden role as increasingly obsolete.

As Neil deGrasse Tyson claims, “The philosopher is a would-be scientist without a laboratory.” In essence, philosophy was once needed to give rise to science, but it is now largely seen as unnecessary.

Philosophy Is the Handmaiden of Ego

Philosophy can serve the ego, meaning one’s philosophy can become a source of the feeling of being special, or, in extreme cases, the most special. This kind of philosophy is untethered from truth as found in divine revelation or the scientific method, and instead serves a “truth” discovered solely by the mind of the special individual.

I’ll spend the most time on this relational alignment because it is the most underdiscussed.

For a “philosopher,” truth may still be claimed to be at the center, but truth is neither Him nor the “correspondence theory of truth,” the leading model among the science-minded, in which one’s understanding of reality is expected to align with empirically evidenced facts. Instead, truth in this context often comes across as impenetrable gobbledygook to most people, and is considered accessible only to him or to others like him—those he philosophizes with.

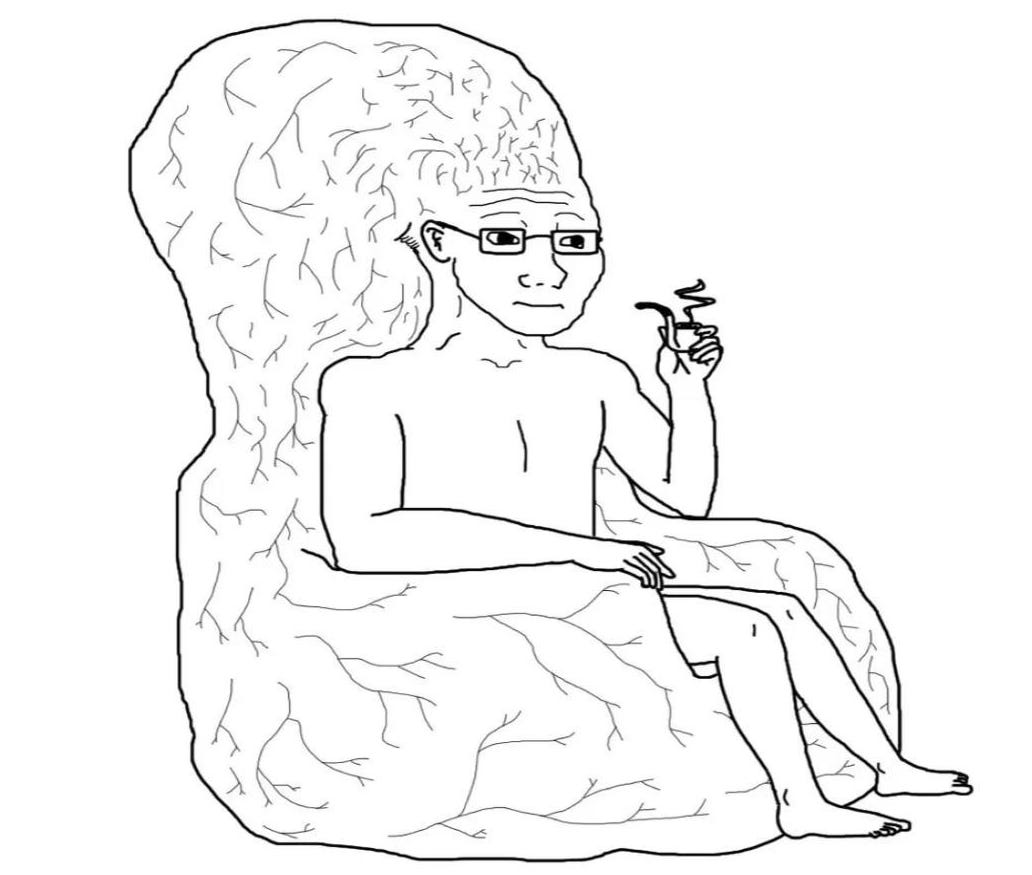

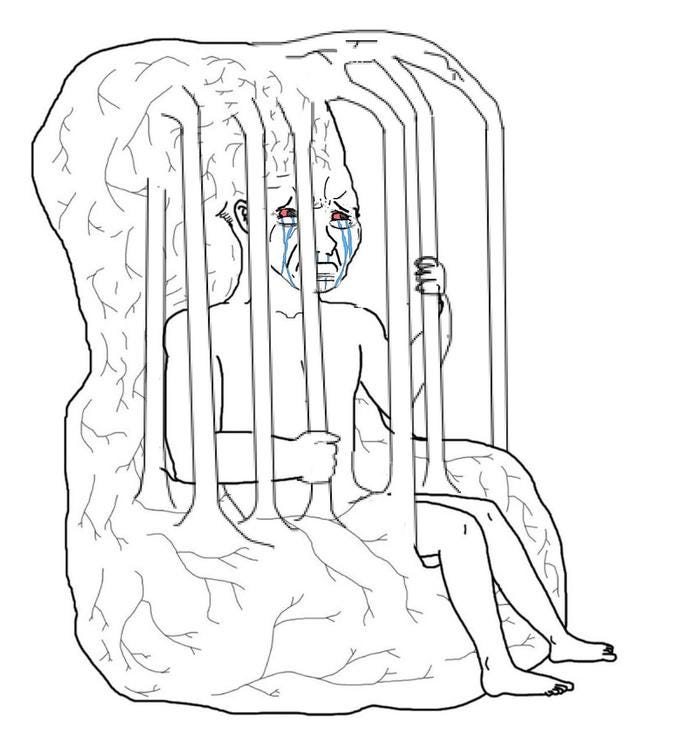

An image that captures this kind of philosophy is the “Big Brain Wojak,” a meme from 4Chan, a website with a high rate of memetic success. I believe this is because its users operate outside the Overton window and often feel they have nothing to lose, which allows them to see things others cannot. Their memes are mocking in tone, yet can also be playful, often pointing out tendencies they themselves possess.

In this light, I’ll be using the Big Brain Wojak as a form of tough love. Tough, in that those who are egoically captured often need humility, or else they risk further humiliation. Love, because their theoretical overcompensation often stems from a lack of love. I know this because, as I indicated in my previous piece, “All Philosophers Are Charlatans,” what I write below is partly confessional.

The Big Brain Wojak meme represents a self-satisfying mode of inquiry that results in an incapacity to navigate reality wisely, whether in practical or relational matters. This is due to the alienating, top-heavy theoretical frameworks they have developed.

If you ever debate one of these “philosophers,” there is a distinct feeling that a simulacrum of you is being created, one that is always easily refuted, because they cannot release their theorized worldview in order to make real contact with yours.

Truly understanding another worldview is too threatening an endeavour because it might expose where they are wrong, and being wrong in even one premise may have a cascading effect, disrupting their ability to carry out even the simplest tasks of life. When challenged, their worldview can become disordered, and their theoretical creation may turn on them.

Unless they submit their inquiry to something larger than their mind, such as tradition based on divine revelation or a peer-tested method for discovering truth, they create a theoretical prison of their own making.

Suffering results.

Luckily, there is a way out.

Philosophy, Crucified

For a time, I assumed theoretical philosophy was synonymous with philosophy itself. This error in thinking changed in 2013 when I discovered practical philosophy through Andrew Taggart, which proved to be a transformational encounter.

I realized that practical philosophy allows one to situate their philosophy in their life, addressing personal, context-sensitive matters that are salient in the here and now. In contrast, theoretical philosophy can be untethered from such concerns, creating layers upon layers of abstraction, which become mental prisons in which the “philosophers,” and those who follow them, may become trapped.

To be clear, there is tremendous value in theorizing about our world, and the theoretical project is a worthwhile one. Of course, not all theoretical philosophy is egoic, but ego-bound philosophizing often appears in theoretical form.

Ultimately, making philosophy a handmaiden to one’s ego is a defence mechanism, serving as a form of ego-protection first and ego-validation second. The manifest result of this is “theoretical bypassing,” where, instead of addressing their core wound through more grounded forms of inquiry, the “philosopher” theorizes away from it, protecting themselves from seeing it and preventing others from seeing it as well. Once their theoretical castles are built, they can then receive validation from them, a kind of validation they are missing because of the wound they refuse to love.

While incorporating practical philosophy can correct for this, philosophy still cannot serve itself. Doing practical philosophy presents its own challenges and can morph into a masturbatory project: endless rumination, overreliance on (im)practical philosophical inquiry, and the neglect of other modes of inquiry, such as coaching and therapy, or, more importantly, spiritual practices found in a wholesome tradition. Philosophy, regardless of whether its orientation is theoretical or practical, needs to know its place.

In essence, philosophy needs to be crucified.

Thanks to my emerging Christianity and an increasingly enriching prayer life, I am biased toward seeing philosophy as the handmaiden of theology. However, I still believe it can help science. It can also help theology and science enter into a right relationship with one another, showing where real tension exists or where the illusion of tension is, and then helping to release it.

Also, despite my criticism of the egoic approach, I am not committing an “ego fallacy.” That is, just because something may stem from a secretly egoic place does not mean it is entirely wrong. In fact, it’s usually partially right.

God works in mysterious ways, and some people are called to discover truth outside a more prayerful or empirical mode of being, venturing beyond established theologies or sciences and arriving at surprising insights. Such philosophies, especially when expressed with a degree of artistry, can be impressive, fascinating, and deeply informative.

While ultimately misguided, ego-fueled philosophizing can have exaptive benefits, in the sense that it provides a confidence boost in one’s mind, in their ability to use it, and in the development of strong thinking. The word “ego” has a bad rap; there is such a thing as a “healthy ego” for a reason. In short, we can learn from the ego, even if it's just to see how interestingly wrong it is.

This closes the series on practical philosophy. Since 2013, when I first discovered it, I have been on a journey to remove childish motives behind my approach to philosophy and to life more broadly. Still, I stumbled along the way, foolishly relying on my version of practical philosophical inquiry more than it deserved.

Only very recently, since my turn toward Christianity, do I feel that inquiry now comes from a whole place.