This entry is part of a five-part series on “terrible communities”: 1. All Communities are Terrible Communities. 2. Terrible Outcomes of Terrible Communities. 3. A Less Foolish Power Literacy. 4. Terrible People in Terrible Communities. 5. An Antidote to Terrible Communities. Appendix. I Am Not Writing to the World: A Guide to Creating "Theory Sketches.”

In the previous entry, I considered the premise "all communities are terrible communities," borrowed from Tiqqun's "Theses on the Terrible Community." I ended the entry by claiming communities can be good and must risk being more terrible before becoming less so.

Once people become aware of terrible communities, they become attracted to change them. "Change communities" arise from this awareness and fall into three categories:

Groups of people engaged in objective change in the external world.

Groups of people engaged in subjective change in the internal world.

Groups of people engaged in intersubjective change in the social world.

Paradigmatic examples include activist communities falling into the first category, spiritual communities in the second category, and “we-space” communities1 in the third one. It would be hard to cleanly place an active example into one of these categories, as most change communities today have all three aspects2. Nonetheless, this conceptual clarification reveals the inherent factors that draw individuals away from terrible communities.

Asking why individuals are attracted to communities centered around change could lead to an explanation highlighting the group's primary intention, often involving a positive transformation in the world. However, the motivating reason is to flee the terrible communities they belong in. To escape being unheard, unseen, and unloved by those they rightfully expect to be heard, seen, and loved by.

When people flee terrible communities unexamined, without sufficient wisdom, great foolishness abounds, with one of the following three terrible outcomes:

“Tyranny of structurelessness” for activist communities.

“Cult states” for spiritual communities.

“Intimacy without friendships” for we-space communities.

All change communities lack "power literacy" to spot the power games at play, with many having an allergy to having power. Without a satisfactory level of power literacy among members and comfort with holding power, one of three terrible outcomes will likely arise.

Tyranny of Structurelessness

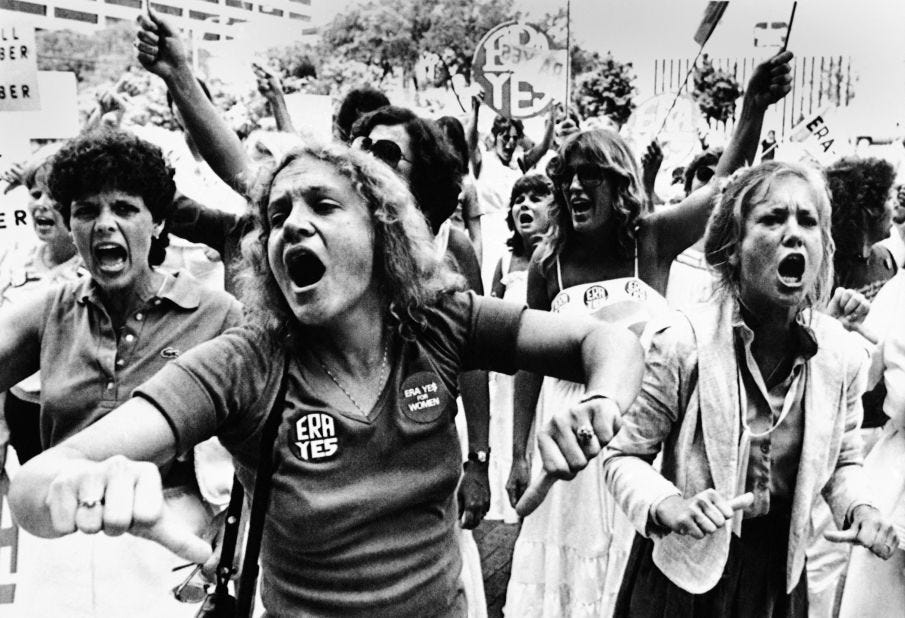

Feminist Jo Freeman wrote the essay “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” in 1970, discussing her experience in the women's liberation movement who engaged in leaderless groups without formal structure in rebellion against what they deemed an oppressive overstructure in society. Such groups descended into power struggles, subduing their effectiveness.

When the pretense of structurelessness exists, structure forms in unacknowledged ways, hence in an unaccountable manner, with a secret elite emerging that denies its own existence. As Freeman describes the nature of such elites, the "most insidious elites are usually run by people not known to the larger public at all. Intelligent elitists are usually smart enough not to allow themselves to become well known."

The people who operate best in the shadows usually have sociopathic tendencies, lack empathy, and are good at manipulating people who do. They weaponize the word community when a sense of community first emerges, preying on the “community hunger” many have, only to grab power and impose their agenda in the shadows.

Many activist groups do not have the societal impact they wish to have because they become enmeshed shitshows, unable to address their internal drama, leaving them ineffective in changing the world. If power illiteracy exists, with a secret allergy toward holding power, change communities confronting the powerful externally will only find themselves internally having an unethical power elite form.

Cult States

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find a change community with too much structure, which happens to people looking to change their internal worlds. People turn toward spiritual communities for this. Instead of power secretly diffused amongst a power elite, it resides openly with one person, usually a man3 who has or claims special abilities.

I will repurpose psychosecurity professional Patrick Ryan’s term “cult state” to describe a communal state with cult-like dynamics. Though not all spiritual communities are cults, those with a central authority and communal living are cult states that can eventually evolve into bona fide cults. Andrew Cohen and his EnlightenNext organization exemplify how well-meaning people can fall into a cult.

In cult states, adherence to the leader naturally emerges, frequently because the members want to be told what to do. Cults form from cult states not solely from the "counterdependent" temperament of the leader but from the "co-dependent" temperament of the members. The former has a non-attached disposition, while the latter has an attached neediness. Without sufficient power literacy, the symbiotic relationship between the two becomes terrible.

Intimacy without Friendships

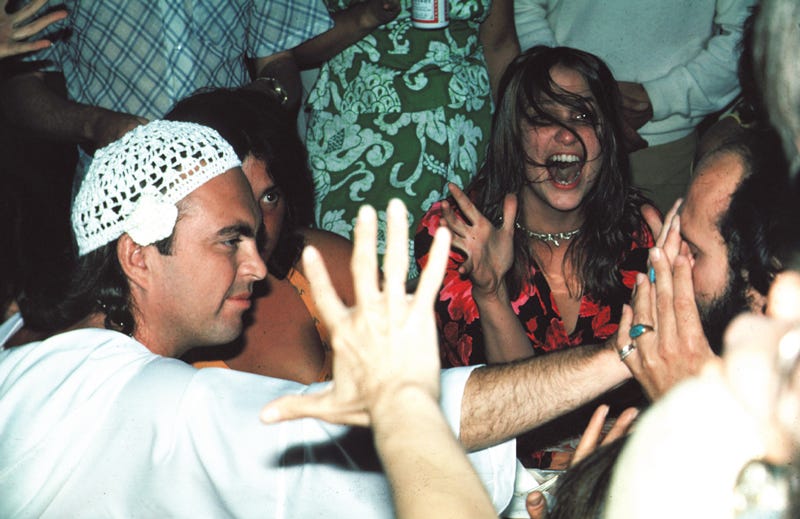

Thanks to the awareness of the terribleness of past activists and spiritual communities, from a Fisherian “Vampire’s Castles” (aka “the left eating/canceling their own”)4 to Buddhistic monastic sex scandals, people are looking for safer options to escape their terrible community. The we-space movement is new and consists of “intersubjective meditation” practices that can engender deep intimacy and a communal sense of oneness.

I have explored many we-space practices: Circling, Authentic Relating, Surrendered Leadership, Collective Presencing, Empathy Circles, Insight Dialogue, Social Mediation, ZEGG-Forum, and Honest Sharing.5 I advocate experiencing these practices, especially when the group members pass a threshold of psychological individuation, as profound states can occur. Circling is the most popular of the we-space practices, and given its popularity, it has received the most criticism. I believe if practiced with care, and with the right people, in the absence of the “culture of Circling” that has become associated with it, Circling can be beneficial, even beautiful. However, I believe the following criticisms are accurate.

The most savage comes from New Right writer

, who called them “Platonic orgies” that allow one to practice fake intimacy, creating “emotional porn stars.” Another criticism comes from Soryu Forall of the Monastic Academy, who claims Circling promotes “intimacy without friendships” and provides a sense of connection with a person without having any responsibility to them. If practiced consistently, Circling will make one “narcissistic and numb.” We-space practices like Circling can quickly become a congregation of intersubjective masturbators, getting off on connective states as escapist copes, with the group's attention reliably collapsing to the most neurotic person.People drawn to these groups, while good-hearted and truth-seeking, are generally naive to power dynamics. Practicing intimacy without friendship only amplifies this naivety, fostering an "idiot compassion"6 with porous personal boundaries, allowing themselves to be enablers rather than compassionate friends. While this last terrible outcome may seem the most benign, these practices will only maintain terrible communities if they are the primary practices people commune around.

***

My analysis of the three change communities leans toward being uncharitable7, focusing on the failure modes with each rather than the positives they can bring. All three aspects of change are needed, and I see these terrible outcomes as public lessons to help good communities form. Highlighting these outcomes is vital to building a "metalanguage of communing" that promotes a "communal literacy" for those looking to start a community or find themselves amid one forming.

However, communal literacy will be impotent without having power literacy. The latter should not be used for people to become little Machiavellians with an unexamined rush to gain more power. It should be used to demystify power, to spot those consciously or unconsciously playing power games in all strata of society, from office politics to parapolitics8. Power literacy helps one exercise power with less foolishness.

As the philosopher Peter Sjöstedt-H writes: "Understanding power empowers." Foremost of all, without power literacy, there will be no answering “the sociopath question”:

How do we deal with people with innate power literacy, who are bent toward self-serving motives and are extremely skilled at manipulating social fields?

Without answering this question, no good communities will form.

In upcoming entries on terrible communities, I’ll address the sociopath question and offer an antidote.

See Cohering the Integral We Space: Engaging Collective Emergence, Wisdom and Healing in Groups for a theoretical introduction to we space practices.

Extinction Rebellion (XR) is a prime example of this. They have particular demands on government policy. Co-founder Gail Bradbrook is influenced by the work of Ken Wilber, recognizing the need for society-wide internal change. XR groups also use we space practices such as Dominic Barter's Restorative Circles.

I predict we will see this changing with more women cult leaders arising. Teal Swan may be an example of this.

Vampire Castle was how the left described “cancel culture” before the phrase cancel culture got captured in the culture war. To see my take on the so-called cancel culture, I still agree with most of my “Cancel Swarm, Cancel Panopticon, and Cancel Extortion” entry.

John Vervaeke and I explored we space practices before The Stoa started. You can watch our conversation on our explorations here.

“Idiot compassion is a great expression, which was actually coined by Trungpa Rinpoche. It refers to something we all do a lot of and call it compassion. In some ways, it’s called enabling. It’s the general tendency to give people what they want because you can’t bear to see them suffering. Basically, you’re not giving them what they need. You’re trying to get away from your feeling of I can’t bear to see them suffering. In other words, you’re doing it for yourself. You’re not really doing it for them.” - Pema Chodron

I often write with the “principle of charity,” bringing forth the most charitable interpretation of arguments. However, sometimes being uncharitable teases out truths hidden in plain sight.

Also known as “deep politics.” These terms are both from Peter Dale Scott, referring to hidden political machinations rather than surface ones, aka what we see with electoral politics or culture war. Parapolitics are usually dismissed alongside more fantastical “conspiracy theories,” an effective power move to conceal power moves in play.