This entry is part of a five-part series on “terrible communities”: 1. All Communities are Terrible Communities. 2. Terrible Outcomes of Terrible Communities. 3. A Less Foolish Power Literacy. 4. Terrible People in Terrible Communities. 5. An Antidote to Terrible Communities. Appendix. I Am Not Writing to the World: A Guide to Creating "Theory Sketches.”

"I miss The Stoa because it was a feeling."

A reader sent the above to me, replying to one of my recent entries on "terrible communities," where I stated The Stoa is not a community and never was. In spirit, I agree with him. The Stoa was a feeling, maybe a "vibe," or perhaps something we collectively imagined.

In Tiqqun’s “Theses on the Terrible Community,” there was a fleeting remark, mentioned almost as an aside, about all the communities that are not terrible:

All the other communities are imaginary, not truly impossible, but possible only in moments, and in any case never in the fullness of their actualization. They emerge in struggles, and so they are heterotopias, opacity zones free of any cartography, perpetually in a state of construction and perpetually moving towards disappearance.

That last sentence resonated: "perpetually in a state of construction and perpetually moving towards disappearance." The Stoa feels like it is always ending and always just beginning. My seeming fickleness is due to a promise I made: when "stewarding" The Stoa, I only follow a particular spirit, moving where it takes me. It usually takes me to the end, only to begin again.

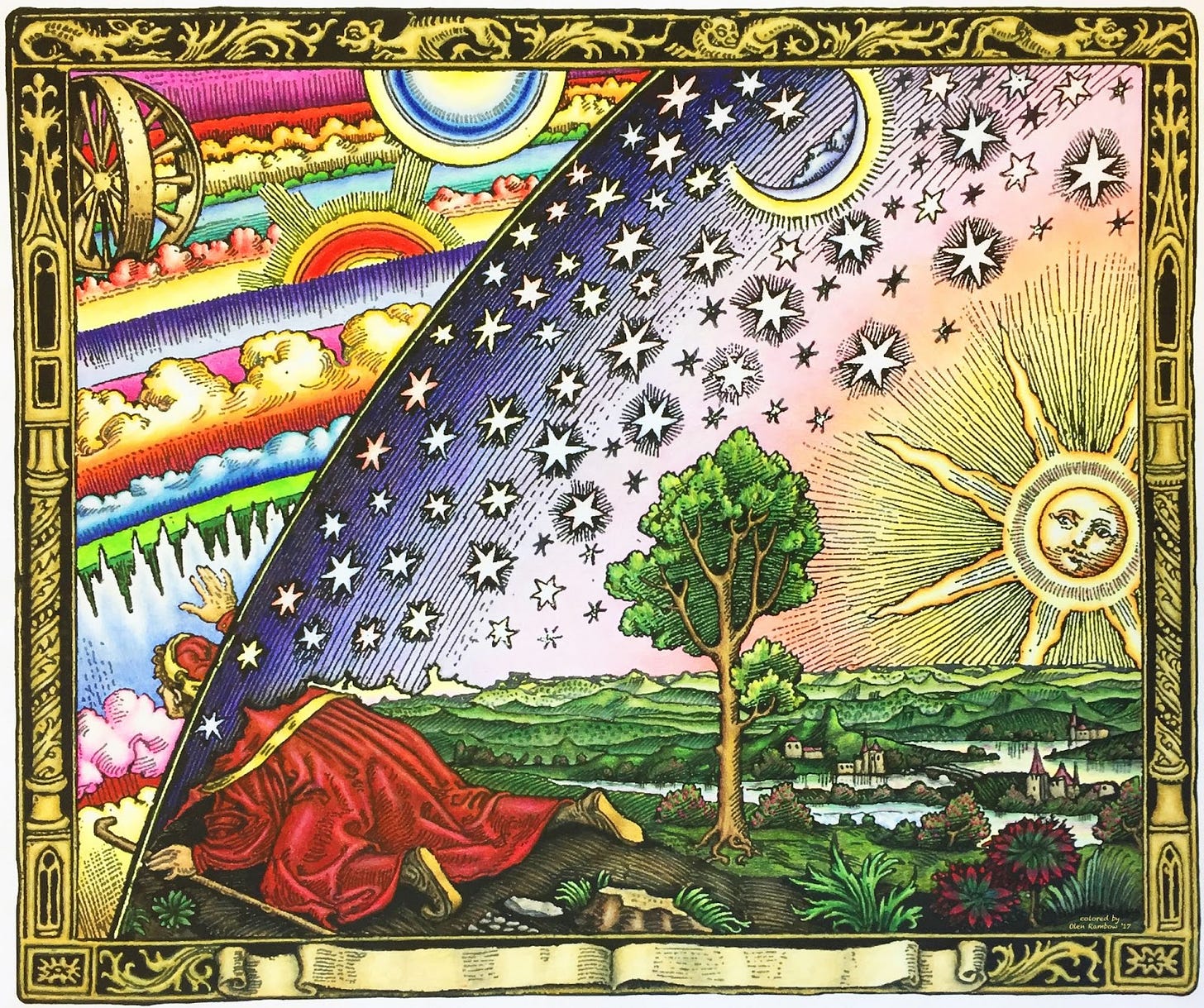

I have a point of contention with the Tiqqun passage, with the use of the word “imaginary.” I believe “imaginal” is the correct phrase. Philosopher Henry Corbin distinguishes between the imaginary and the imaginal; the former is a realm of mental images, escapist fantasies, and pure imagination unconnected with reality. The latter, what he referred to as “mundus imaginalis,” is a realm distinct from mental and physical ones, an in-between world bridging the subjective and the objective, where daemons are guides, myths are true, and archetypes are alive.

The imaginal gives access to a world always in front of us, requiring an uncommon way of perceiving the wisdom it offers, what Corbin calls "the psycho-spiritual senses" or what Christians call "spiritual sight."1 Interacting with the imaginal world has alchemic effects on our "real" one.

Does such a realm exist? I do not know if such a claim can be proven, yet I've encountered enough mysterious things that whisper it true.

***

In previous entries on terrible communities, I wrote about the "sociopath question," archetypal malevolent sociopaths ("people of the lie"), and petite sociopaths commonly found in social settings. I am concerned with those with sociopathic tendencies because all it takes is one person to ruin a communal vibe, making things difficult and wrecking a group's potential.

In the book Political Ponerology, psychiatrist Andrzej Łobaczewski argued we live in a “pathocracy,” a political system characterized by being ruled, openly or secretly, by individuals with personality disorders. These sociopathic leaders lack empathy and a moral compass, providing them a "fearless dominance"2 that puts them in positions of societal power. When in power, they use societal systems to their advantage and to the people's disadvantage. Like leeches, they extract resources and the human spirit for myopic gains, creating a corrupt system that corrupts us.

A "trickle-down sociopathy" occurs; to succeed in the current system, people justify cultivating maladaptive sociopathic behaviors, preventing virtue from forming. The Latin motto gets adopted en mass: Mundus vult decipi, ergo decapitator, translated as, “the world wants to be deceived, so let it be deceived.” Lying, bullshitting, and paltering3 are ways to be effective in the world. Telling the truth truthfully, in the spirit of truth?4 Not so effective.

The sociopaths won—full-spectrum dominance. We are playing their game; they are not playing ours. We are collectively dispirited; imagining a new world is discouraged as childish, a refusal to grow up. Instead, we accept compromised conditions, adulting into the world as is. There's an appealing aspect to embracing this compromise, as we open ourselves to the movement of spirit, only to experience defeat after defeat.

What if this compromise is bullshit, though? What if we are playing the long game? What if what is needed is some imagination?

***

I promised to conclude this series of terrible communities with a proposed antidote. My response thus far has been simple: friendships of virtue. Bringing back friendships of virtue has been an obsession of mine for as long as I can recall.

Aristotle proposed three types of friendships: utility, pleasure, and virtue. Utility is based on benefit, pleasure is on enjoyment, and virtue is on mutual growth in goodness. He argued friendships of virtue are rare and demand time and intimacy, while friendships of utility and pleasure are common, seen in work, leisure, and now on digital platforms.

Such friendships are of course rare, because such men are few. Moreover they require time and intimacy. People who enter into friendly relations quickly have the wish to be friends, but cannot really be friends without being worthy of friendship, and also knowing each other to be so; the wish to be friends is a quick growth, but friendship is not.

My argument for friendships of virtue as an antidote for terrible communities is simple:

Premise 1: The presence of friendships of virtue is essential for achieving a community of virtue.

Premise 2: Friendships of virtue form the fundamental building blocks, the "relational atom," of a community of virtue.

Conclusion: Thus, the requirement for friendships of virtue as the foundational element is crucial to create a community of virtue.

I stopped thinking of my close friends as friends of virtue. It is too demanding on them. Too unfair. Experiment after experiment, I have pressed my friends and myself toward discovering the conditions to bring such friendships about. What arrogance I had to deem myself virtuous enough to cultivate such friendships. Friends of virtue do not exist in the real world. You will not find them in terrible communities where sociopaths dominate.

If you think you can find them, you'll only be lying to yourself, disappointing others in the process. I am tired of lying to myself. I am tired of disappointing others. I am tired of the pressure to copy the traits of those who rule over us. I have failed so many times; my obsession feels impossible. Yet, the impossible might be the wise starting point.

Kids have imaginary friends, fictional playmates created in the imaginary realm. Such friends help improve social skills, creativity, and overall cognitive maturation.5 Adults who refuse to compromise their souls can take inspiration from this phenomenon, venturing into the impossible to cultivate imaginal friends in imaginal realms.

At its most mystical, The Stoa is a feeling, a vibe, something we collectively imagine. It is a place where souls pass through realms unseen, in front of our eyes, nodding to one another with knowingness about worlds existing on the other side of our imagination. Friends of virtue live there as well, I've seen them, and they offer us insights on how to one day meet them.

We can only imagine.

“I would like to elaborate a bit, specifically on the question: what exactly does “seeing the unseen,” or spiritual sight, entail? Seeing the unseen means to gain a subtle “uplink” to the higher world, the world of Spirit, and to be able to discern the spiritual reality, the hidden meaning, behind the material world. This then leads to better decisions and actions—decisions based on “the things of God” as opposed to “the things of man,” as Mark’s Jesus expressed the Pauline teaching.” - from

’s “Spiritual Sight: How to See the Unseen.”“Fearless dominance captures a broad dimension of boldness encompassing physical fearlessness, interpersonal poise and potency, and emotional resilience. High levels of fearless dominance alone are not sufficient for psychopathy, although they may map largely onto Cleckley’s “mask” of seemingly healthy adjustment. Fearless dominance is linked to superior executive functioning, suggesting a potential point of convergence with the moderated-expression model. Recent studies suggest that fearless dominance may be a marker of the successful features of psychopathy and may bear important implications for leadership.” - from "Successful Psychopathy: A Scientific Status Report" (Lilienfeld, Watts, and Smith)

“One of their techniques is called paltering, which is stating true facts in such a way that consciously engenders a false impression, with an intent to deceive. This is similar to Harry Frankfurt’s notion of “bullshit.” When somebody is bullshitting you, they are not being truthful, but they may speak what is true at times, without caring about the truth, and they do this with the intent to persuade.” - from my article, “Where Truth Is Found.”

I consider three types of truths: Truth = The “correspondence theory of truth,” having your words correspond with reality. Truthfulness = Speaking what you believe to be true, even if it turns out not to be the truth. The Spirit of Truth = “Even the Spirit of truth; whom the world cannot receive, because it seeth him not, neither knoweth him: but ye know him; for he dwelleth with you, and shall be in you.” - John 14:17.

“Overall, the potential that ICs [imaginary companions] possess for enhancing ToM [theory of mind], creativity, social skills, and wellbeing, as well as the ways in which the social and environmental context influence children’s creation of ICs, certainly merit further exploration. Much of the value of IC research lies in its potential to center children’s expe- riences and recognize the significance of their play as external forces seek to undermine it, and future inquiry may be guided by this goal.” - from “A Review of Imaginary Companions and Their Implications for Development” (Armah and Landers-Potts).